Happily Ending The HIV Epidemic

By David A. Wohl, MD – January 9, 2012

In 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) adjusted their estimate of the annual number of new HIV infections in the US from approximately 40,000 to 56,000 after applying improved methods for detecting and extrapolating HIV incidence. It was the adjustment heard around the world. That the incidence of HIV had been underestimated and was stagnant was a literal wake-up call for those whose job it is to think about how best to stop people from spreading their virus to each other. While the media and prevention experts took notice, policy-makers took action and charted a new course for interventional research to prevent HIV transmission. Following these prevention dollars, prevention research shook its sleepy head and got busy.

Four years later we have seen a renaissance in HIV prevention research with creative approaches being tested in the US and abroad. The fruits of these labors, most notably, include studies that have combined the understanding of human behavior with an appreciation that antiretrovirals work really well at shutting down the replication of HIV. Antiretrovirals are being used in novel and imaginative ways: compounded into vaginal microbicides, administered to high risk uninfected people as a pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and given to HIV+ patients to lower their HIV viral load, and therefore, their infectiousness.

But, what will it take to really end HIV/AIDS? Modeling exercises show that only with major reductions in transmission can the HIV epidemic be expected to dry up. Such simulations are guilty of simplicity and have a hard time accounting for the complex interaction of biological and social forces.

That said, there is certainly a sense that stopping HIV is not fantasy and that we are on a path that will lead to just that. For me, the finding (by NC’s own Dr. Myron Cohen) that HIV therapy administered to HIV+ individuals greatly reduces their ability to infect partners is major and means that the seeds of the stemming of the HIV epidemic may have already been sowed with each prescription of ART given to a person with HIV infection. The problem is too few have been treated.

That said, there is certainly a sense that stopping HIV is not fantasy and that we are on a path that will lead to just that. For me, the finding (by NC’s own Dr. Myron Cohen) that HIV therapy administered to HIV+ individuals greatly reduces their ability to infect partners is major and means that the seeds of the stemming of the HIV epidemic may have already been sowed with each prescription of ART given to a person with HIV infection. The problem is too few have been treated.

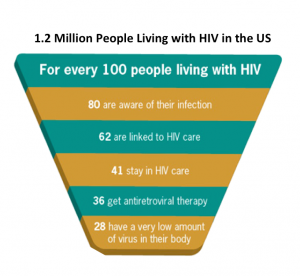

A few weeks ago, the CDC released another important and sobering important analysis this time estimating that of the 1.2 million people living with HIV infection in the US, 36% are receiving HIV therapy and while most achieve viral suppression, this is only 26% of all those infected. Therefore, three quarters of HIV+ people in the country are not being treated and have a much higher potential to infect others when engaging in risky behaviors. Details of this report can be found here.

Clearly, there is more to ending HIV than using more ART. Yet, broader use and adherence to HIV therapy is essential and within our capabilities to accomplish. Foremost, for the majority of infected persons aware of their HIVseropositive status need to treated and maintained on therapy. Next, we must reach the 1 in 5 people with HIV do not know they are HIV+. Testing more people at risk for infection, starting HIV therapy early, and supporting ART adherence can make a sizable dent in the incidence of HIV. Throw in some PrEP for some very high-risk men, microbicides for women (and eventually guys too), seeking and destroying other STIs that increase risk of getting and giving HIV, along with good old behavioral interventions and you got a Highly Active Prevention PartY. Yep, that is HAPPY.

Next, who caught HIV today.

Check out my top 10 HIV clinical developments of 2011 at The Body.