Cook lab researchers publish a paper in Nature Cell Biology. The finding presents a possible explanation for why so many cancers possess not just genomic instability, but also more or less than the usual 46 DNA-containing chromosomes.

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – The foundation of biological inheritance is DNA replication – a tightly coordinated process in which DNA is simultaneously copied at hundreds of thousands of different sites across the genome. If that copying mechanism doesn’t work as it should, the result could be cells with missing or extra genetic material, a hallmark of the genomic instability seen in most birth defects and cancers.

University of North Carolina School of Medicine scientists have discovered that a protein known as Cdt1, which is required for DNA replication, also plays an important role in a later step of the cell cycle, mitosis. The finding presents a possible explanation for why so many cancers possess not just genomic instability, but also more or less than the usual 46 DNA-containing chromosomes.

The new research, which was published online ahead of print by the journal Nature Cell Biology, is the first to definitively show such a dual role for a DNA replication protein.

“It was such a surprise, because we thought we knew what this protein’s job was – to load proteins onto the DNA in preparation for replication,” said Jean Cook, PhD, associate professor of biochemistry and biophysics and pharmacology at the UNC School of Medicine and senior study author. “We had no idea it also had a night job, in a completely separate part of the cell cycle.”

The cell cycle is the series of events that take place in a cell leading to its growth, replication and division into two daughter cells. It consists of four distinct phases: G1 (Gap 1), S (DNA synthesis), M (mitosis) and G2 (Gap 2). Cook’s research focuses on G1, when Cdt1 places proteins onto the genetic material to get it ready to be copied.

In this study, Cook ran a molecular screen to identify other proteins that Cdt1 might be interacting with inside the cell. She expected to just find more entities that controlled replication, and was surprised to discover one that was involved in mitosis. That protein, called Hec1 for “highly expressed in cancer,” helps to ensure that the duplicated chromosomes are equally divided into daughter cells during mitosis, or cell division. Cook hypothesized that either Hec1 had a job in DNA replication that nobody knew about, or that Cdt1 was the one with the side business.

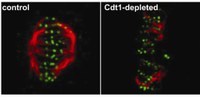

Cook partnered with Hec1 expert Edward (Ted) D. Salmon, PhD, professor of biology and co-senior author in this study, to explore these two possibilities. After letting Cdt1 do its replication job, the researchers interfered with the protein’s function to see if it adversely affected mitosis. Using a high-powered microscope that records images of live cells, they showed that cells where Cdt1 function had been blocked did not undergo mitosis properly.

Once the researchers knew that Cdt1 was involved in mitosis, they wanted to pinpoint its role in that critical process. They further combined their genetic, microscopy and computational methods to demonstrate that without Cdt1, Hec1 fails to adopt the conformation inside the cells necessary to connect the chromosomes with the structure that pulls them apart into their separate daughter cells.

Cook says cells that make aberrant amounts of Cdt1, like that seen in cancer, can therefore experience problems in both replication and mitosis. One current clinical trial is actually trying to ramp up the amount of Cdt1 in cancer cells, in the hopes of pushing them from an already precarious position into a fatal one.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Study co-authors from UNC were Dileep Varma; Srikripa Chandrasekaran; Karen T. Reidy; and Xiaohu Wan.