Policy Brief

Executive Summary

North Carolina does not enforce the federal minimum sale age of 21 for tobacco products. As a result, underage North Carolinians, particularly children in our schools, are getting increasingly addicted to tobacco, including e-cigarettes and vapes.

were 21. Aligning state law with federal T21 policy

along with other evidence-based policies such as

tobacco retail licensing, bans on promotions, and

supporting schools will reduce youth tobacco use

in NC and keep youth safe from the life-long health

risks of tobacco.

Scope of the Problem: What is the State of Youth Tobacco Use in NC?

Among those who use tobacco, youth are exhibiting behaviors of addiction at high rates: 27% of NC high school and 20% of NC middle school tobacco users want to use a tobacco product within 1 hour of waking up. 1 in 4 high school and 1 in 3 middle school tobacco users in NC find it hard to get through the school day without using an e-cigarette.1

Once youth are addicted, they have a very hard time quitting tobacco – 64% of NC high school and 68% of middle school students who use tobacco have tried to quit and failed.1

Nationally, e-cigarettes have been the most popular tobacco product among youth for 10 years in a row; 1 in 4 youth e-cigarette users vape at least once a day.3 It is far too easy for underage people in NC to obtain e-cigarettes: 59% of NC youth under 21 who used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days purchased them at a retail location. Over 43% of NC teens get their vapes from a friend/peer.4

E-cigarettes are designed to be accessible to youth by being cheap, disposable, and made with flavors. The most common type of e-cigarettes used by middle and high schoolers are disposable and the majority of youth who vape are using flavored e-cigarettes, including fruit, dessert, and menthol flavors.1

1 in 8 NC high-schoolers regularly use tobacco.1

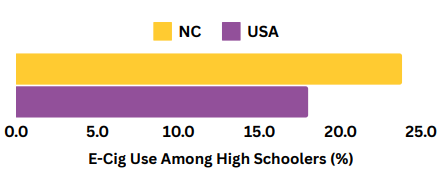

23.8% of NC high-schoolers used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days (compared to only 18% nationally).1

Adult Perspectives: What do Parents and School Staff Think?

Based on interviews with 17 School Resource Officers (SROs) across NC, SROs perceive youth vaping as a serious public health problem.

“…kids don’t really have the cognitive brain function to make that logical choice until they are 21 to 25 years old. So, why are we letting them make the choice at a younger age if we know they aren’t fully developed to where they can make that choice?” (SRO from Coastal Plains region)

Among a sample of NC parents, 84% consider any e-cigarette use as risky or dangerous for their child.

88% of surveyed parents believe that e-cigarettes are as addictive or more addictive than tobacco cigarettes.

Policy Recommendations: How Can Policymakers Support a Tobacco-Free Generation

Institute tobacco retail licensing (TRL)

Much like alcohol licensing, 34 states require retailers to obtain a license to sell any tobacco product, and 6 have TRL that does not cover e-cigarettes. NC is one of 10 states that allows any tobacco product to be sold without a license.

TRL is an essential regulatory tool that keeps retailers accountable for repeated underage sales violations. Licensing fees can fully fund the cost of both the licensing program and enforcement of public health regulations such as flavor restrictions and the prohibition of product discounts.7 8

TRL have been shown to reduce initiation of tobacco use and the number of tobacco sellers, particularly near schools.9 10

Place limits on retailer promotions

Tobacco companies now direct 98% of their advertising budgets to the point-of-sale (POS) retailing space, primarily using signage, in-store advertising, and preferred placement within displays.

Exposure to such advertising is known to increase the initiation of tobacco use among youth and to make it more difficult to quit.13

Promotions and discounts such as “buy-one-get-one” are associated with youth usage. Bans on promotions for tobacco products, along with an explicit flavoring ban, effectively reduced e-cigarette use among high schoolers in Providence, RI by 7% in 1 year.

Establish and enforce state-level Tobacco 21 laws

Across the country, 41 states have passed their own laws raising the minimum legal sales age (MLSA) to 21. The federal Tobacco 21 law (T21) goes unenforced in states like NC that have not yet raised the MLSA to 21.

Retailer compliance checks take place across the state of NC to determine how many tobacco retailers are selling products to underage buyers. Compliance reporting indicates that 22% of retailers sold tobacco products to underage youth, as of 2024.

Enforcement of T21 is a highly effective way to reduce youth tobacco use. In CA, the rate of underage sales reduced to nearly half in the year after the state T21 law went into effect [5]. Aligning state and federal MLSA laws has provided clarity and efficiency for retailers and enforcement officials.

Repeal of preeemption laws

Preemptive tobacco laws prevent localities from adopting standards beyond those which the state sets. These can include bans on flavored products, licensing requirements, minimum-required distance of retailers from schools, and much more.

Such preemptive laws prevent localities from implementing new evidence-based policies to reduce youth tobacco use, such as enforcement of the federal T21 policies. These laws also force state legislatures to create one-size-fits-all regulations for the entire state.15 16

Summary

Knowing that over 90% of smokers began using tobacco before they turned 21 underscores the need to use every policy lever to prevent youth tobacco use. The General Assembly can help reduce youth exposure to and use of e-cigarettes and other tobacco products by amending state G.S. 14-313 to officially make the MLSA 21 years of age in NC law. Aligning with the federal Tobacco21 law in NC will form the foundation for all other state tobacco policy going forward, creating clarity for minimum age enforcement. There is no more important policy to ensure NC’s next generations are tobacco-free.

Policy Brief PDF VersionReferences

- NC Youth Tobacco Survey (NCYTS), 2022

- CDC Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance System (YRBSS), 2021

- FDA National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS), 2023

- NCDHHS Tobacco Use Initiation & Access Fact Sheet

- Zhang X, Vuong TD, Andersen-Rodgers E, Roeseler A. Evaluation of California’s ‘Tobacco 21’ law. Tob Control. 2018 Nov;27(6):656-662

- Marynak K, Mahoney M, Williams KS, Tynan MA, Reimels E, King BA. State and Territorial Laws Prohibiting Sales of Tobacco Products to Persons Aged <21 years – United States, December 20, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69:189-192

- Ackerman A, Etow A, Bartel S, Ribisl KM. Reducing the Density and Number of Tobacco Retailers: Policy Solutions and Legal Issues. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017 Feb;19(2):133-140

- Wooten H, McLaughlin I, Chen L, Fry C, Mongeon C, Graff S. Zoning and licensing to regulate the retail environment and achieve public health goals. Duke F L & Soc Change. 2013;5(65):70–88.

- Coxe N, Webber W, Burkhart J, Broderick B, Yeager K, Jones L, Fenstersheib M. Use of tobacco retail permitting to reduce youth access and exposure to tobacco in Santa Clara County, California. Prev Med. 2014 Oct;67 Suppl 1:S46-50

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. Printed with corrections, January 2014.

- Ma, Haijing et al. “Trends in Cigarette Marketing Expenditures, 1975-2019: An Analysis of Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Reports.” Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco vol. 24,6 (2022): 919-923. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntab272

- Robertson, Lindsay et al. “A systematic review on the impact of point-of-sale tobacco promotion on smoking.” Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco vol. 17,1 (2015): 2-17.

- Andrews, M. E., Cooper, N., Mattan, B. D., Carreras Tartak, J., Paul, A. M., & Falk, E. B. (2022, July 12). Causal Effects of Point-of-Sale Cigarette Promotions on Smokers’ Craving: Effects of Price Promotions and Subjective Social Status.

- Pearlman DN, Arnold JA, Guardino GA, Welsh EB. Advancing Tobacco Control Through Point of Sale Policies, Providence, Rhode Island. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:180614

- Halvorson-Fried, Sarah M et al. “Evidence-Based Point-of-Sale Policies to Reduce Youth Tobacco Use in North Carolina.” North Carolina medical journal vol. 83,4 (2022): 244-248. doi:10.18043/ncm.83.4.244

- Kang JY, Kenemer B, Mahoney M, Tynan MA. State Preemption: Impacts on Advances in Tobacco Control. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2020 Mar/Apr;26 Suppl 2, Advancing Legal Epidemiology:S54-S61

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2014.