Patient Stories: Georgia Mae Braddy

A hole inside a heart. A tiny heart. A heart the size of an infant’s fist, with a hole the size of a penny. A hole that helped to keep a little girl alive. Georgia Mae Braddy is, without doubt, a fighter. At four months old, she has already undergone three major surgeries, one of which took place while she was still in utero. This is her story, but it is also the story of a team of UNC doctors and comprehensive caregivers in the departments of cardiothoracic surgery, neurosurgery, and maternal-fetal medicine who worked tirelessly and diligently in coordinated effort to save her life.

At 20 weeks of pregnancy Carmen Braddy, a pediatric nurse, and her husband, Will Braddy were informed that their daughter had Myelomeningocele Spina Bifida, a birth defect in which the spinal cord does not develop properly. The condition involves issues with the spinal cord and nerves, meaning that her little girl may not be able to kick her legs or move her lower limbs, she may never be able to ride a bike or learn to roller skate. Eighty percent of children in this group will develop hydrocephalus, a build-up of cerebrospinal fluid in the cavities deep inside the brain. It was a terrifying diagnosis for the family, but there were options available to them.

Myelomeningocele, the lesion “opening” on the spine, can be repaired in two ways. The first is a surgery that takes place after the child is born, the back is open, nerves of the spine are exposed on the skin and then closed. The other option for babies diagnosed with Myelomeningocele Spina Bifida is a surgery done in utero. This allows the doctors to close up the spinal cord and nerves in the spine as the child is still developing and gives them a better chance of warding off the development of hydrocephalus as well as the possibility of maintaining some lower body function.

Carmen’s doctors at Duke referred the family to the UNC Medical Center, the only facility in the state of North Carolina and one of the few in the Southeastern United States that performs prenatal Myelomeningocele Spina Bifida surgery.

“When Duke first referred us to UNC for the surgery,” Carmen explains, “I told my husband, no way, I don’t want them messing with my child while she’s still inside of me. Maya Lindley, a coordinator with Maternal and Infant Health at UNC, contacted me to discuss the procedure and we had a conversation that lasted over an hour. After I hung up with her I just knew, I changed my mind, I was definitely going to do it just by learning the facts, the benefits and how this could potentially make her (my baby’s) quality of life better.”

On March 13, 2018, Carmen and her unborn child underwent surgery. Dr. William Goodnight, Associate Professor, and Maternal-Fetal Medicine doctor performed Carmen’s part of the surgery, creating an incision from her belly button to her pelvic bone. He positioned the baby and held her as Dr. Scott Elton, Division Chief of Pediatric Neurosurgery, completed the Myelomeningocele repair.

“We have a multidisciplinary team of doctors under one roof that come together to care for both the mother and her child,” says Dr. Elton. “Even before we ever get to surgery the parents meet everybody as a family, they see their team so everyone can explain what their part in the story is. This includes neurosurgery, maternal-fetal medicine, NICU, orthopedics, urology, and rehab. We want to make sure the parents are informed, empowered and feel supported throughout the entire process because they have become part of our family, we will see that child grow over the next eighteen years. ”

After the surgery, Carmen was on bed rest for the remainder of her pregnancy but made the trip every Tuesday for an ultrasound to check on her baby’s progress. On May 30, Carmen and her family checked in to UNC for their scheduled C-Section. Georgia Mae Braddy was born at 6 pounds, .5 ounces, 19 inches in length. “Everyone was so impressed when she came out kicking and moving her legs because we weren’t even sure she would be able to do that,” recalls William Braddy, Georgia Mae’s father.

After five days in the hospital, the Braddy family was discharged and headed home. Twenty days later, however, things took another turn. The family was going about their normal life, preparing dinner, and taking selfies with their 4 year old son, Emmett. Georgia Mae was nestled in her bouncer as the family scurried around the kitchen. Dad went to check on her, putting his hand on her chest, noticing something wasn’t right. He immediately called out to Carmen that she wasn’t breathing. Carmen rushed over and started actions to try and revive her, finally laying her down on the couch to lift up her neck to improve oxygen flow. As paramedics arrived, Georgia Mae had started to breathe again, but everyone knew something was wrong; she was rushed back to UNC Medical Center.

“The doctors started rolling in, and in no time I felt like I was in a movie scene. Her oxygen levels were dropping rapidly,” says Carmen. “They asked me to sit down in a chair, and a chaplain sat next to me. All these people ran in; they had the crash cart, the doctors were at the head of the bed intubating her. I was crying but a part of me, I guess the nurse side of me, noticed that everything was so coordinated. Everybody knew what they were supposed to do. I just remember it as controlled chaos.”

“The doctors started rolling in, and in no time I felt like I was in a movie scene. Her oxygen levels were dropping rapidly,” says Carmen. “They asked me to sit down in a chair, and a chaplain sat next to me. All these people ran in; they had the crash cart, the doctors were at the head of the bed intubating her. I was crying but a part of me, I guess the nurse side of me, noticed that everything was so coordinated. Everybody knew what they were supposed to do. I just remember it as controlled chaos.”

“A million things were running through my head,” Carmen recalled. “When she was in the ED before they intubated her, Dr. Daniel Park, I’ll never forget him, he put the ultrasound machine on her heart and said ‘her heart is enlarged,’ and we just didn’t know what that meant.”

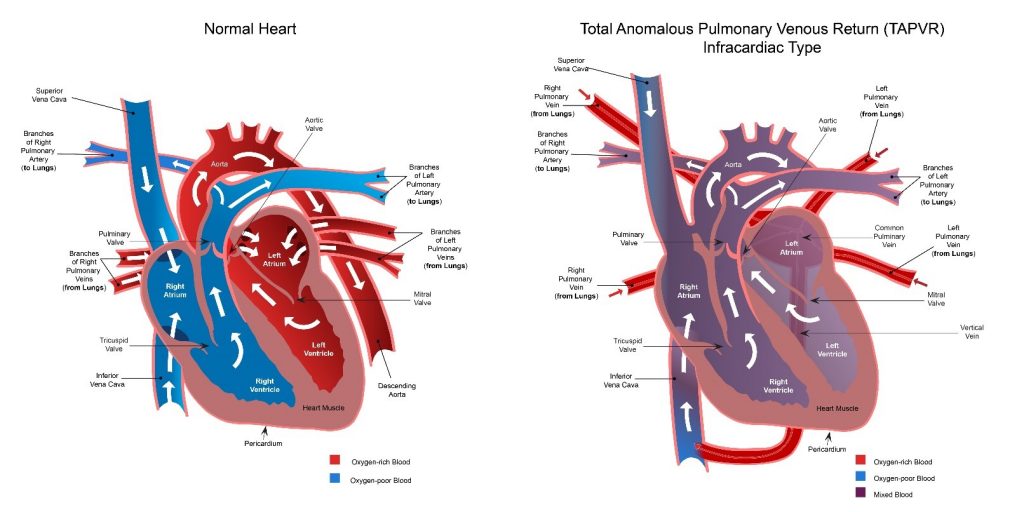

Georgia Mae was transferred to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). After undergoing tests including an echocardiogram, she was diagnosed with TAPVR, Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Return. TAPVR is a rare congenital malformation in which all four pulmonary veins do not connect normally to the left atrium of the heart. Instead, the four pulmonary veins drain abnormally to the right atrium (right upper chamber in the heart) by way of an abnormal (anomalous) connection.

Dr. Mahesh Sharma, Chief of Congenital Cardiac Surgery and Co-director of the NC Children’s Heart Center explains her condition a little more simply. “That means the veins that carry oxygenated blood back from the lungs, to the left side of the heart so that blood can be pumped out through the aorta into the body, for the brain, kidneys, and other vital organs doesn’t make that connection. The blood was instead routed through the liver, to the right side of her heart and then inside the heart, because she had a hole, the blood was mixing. That blood mixture was what was keeping her alive. When she arrived at the hospital, the channel that was connecting the blood to the heart was starting to get narrowed and so that’s when she was having more symptoms.”

Doctors also performed a standard brain MRI, concerned about Georgia Mae’s lack of oxygen during the ordeal and pre-existing neurologic condition. Once all the test results came back, the PICU assistant nurse manager came into the room informing the family that the doctors needed to talk with them about the next steps. “I freaked out,” Carmen remembers, “she brought in five chairs, and I looked at my husband, and I said this is not good.”

Dr. Timothy Hoffman, Chief of Pediatric Cardiology and Professor of Pediatrics along with Dr. Sharma sat down with the family. “They told us that they received the results of her brain MRI,” explains Carmen, “it showed where she had a brain injury from being hypoxic, a condition caused by a lack of oxygen to the brain that occurred the day before when she stopped breathing.”

Due to the brain injury, the procedure of correcting the heart defect created a higher risk for Georgia Mae. The doctors had to take into account more neurological complications including possible stroke and seizures. During the surgery, Georgia Mae would be hooked up to the heart-lung machine to stop her heart and her circulation for short period of time in which blood flow to her brain would be limited. Dr. Sharma, as lead surgeon, and Dr. Michael Mill, assisting him, then would connect the pulmonary veins correctly to the heart and then fix the hole with a patch.

“They wanted to know if we wanted to continue with the heart surgery.” Recalls William “We told them to do everything they can for her. At that point, it almost seemed like the risks outweighed the benefits of the surgery. They were very concerned about it but as soon as they got up, Dr. Sharma came up to me, he was the only one, he shook my hand and said, ‘I’ll take care of her.’ ”

The parents said their “we’ll see you later’s” to their baby girl as she was wheeled into the operating room. At 22 days old, Georgia Mae was headed into her second surgery. After seven hours of surgery, Dr. Sharma walked into the waiting room and gave the family the good news; the surgery was a success. Their baby girl had been able to push through, and the family was able to go back and be with her.

“Georgia Mae’s diagnoses and medical care was extraordinarily complex,” says Dr. Sharma. “The dedication of the care team at UNC Children’s Heart Center along with the multidisciplinary involvement of our other specialists and partnership with her family allowed for her to not only survive, but thrive.”

“We now know this condition is rare,” says William, “especially in her case because she made it so long after birth without it being caught. We learned after all of this that babies with this heart defect don’t normally make it more than 24 hours after birth…she made it twenty-one days. We felt lucky. I felt relieved that he (Dr. Sharma) was the surgeon. I feel like I know him now. It’s a big relief. He’s been wonderful. Everyone has been so wonderful.”

Georgia Mae was in the hospital for seven weeks as she recovered, her mother rarely leaving her side. “For the most part I was with her 24/7,” explains Carmen. “I never went home so I could take care of her. I knew she was in great hands, the people in the UNC Medical Center PICU were absolutely wonderful, and I owe her life to them; the nurses, the doctors, everybody was just amazing. However, there is nothing like the care a mom can give her child; I was able to give her baths, sing to her, talk to her, and be with her as she got stronger every day.”

After being discharged, Georgia Mae continued to come into the hospital for routine checkups. In August during her latest neurosurgery checkup, it became clear that she would need another surgery, this time on the brain. She had in fact developed Hydrocephalus, which was causing a build-up of pressure on her brain and skull like a balloon slowly being blown up.

Georgia Mae’s parents chose to allow Dr. Elton and his team to perform a new, state of the art procedure known as endoscopic third ventriculostomy with choroid plexus cauterization (ETV/CPC). They wanted to forego implanting a brain shunt hoping it would be a better outcome for her. The brain surgery was successful, going smoothly and efficiently. At her most recent doctor visit, her team at UNC Medical Center was very happy with her progress and continued improving health.

Through every roadblock in Georgia Mae’s short life, the team at UNC Medical Center worked side by side to provide her and her family with the highest level of care available. They were with the family during each step, educating them and making sure they felt supported during this process. Due to her condition, Georgia Mae will continue to come in to see the doctors at UNC Medical Center as she ages and develops, meeting new milestones in her life, so they can monitor and make sure she achieves those successes.

“When you step back, and you look at what North Carolina Children’s Hospital offers,” says Dr. Elton, “we operated on a pregnant mother, on her unborn child, with five different teams in play supporting them. Georgia Mae then had a cardiac event, and again we provided comprehensive pediatric cardiothoracic care, all under one roof. She then required hydrocephalus treatment, and we were back to complex Spina Bifida management. It all worked because it’s what we do here, it’s who we are -providing the most complex and comprehensive care for children.”

“When you step back, and you look at what North Carolina Children’s Hospital offers,” says Dr. Elton, “we operated on a pregnant mother, on her unborn child, with five different teams in play supporting them. Georgia Mae then had a cardiac event, and again we provided comprehensive pediatric cardiothoracic care, all under one roof. She then required hydrocephalus treatment, and we were back to complex Spina Bifida management. It all worked because it’s what we do here, it’s who we are -providing the most complex and comprehensive care for children.”

To continue to follow Georgia Mae’s story, please check out her Facebook page here