UNC Center for Transplant Care utilized kidney paired donation, connecting strangers from across the country, to help a mom save the life of her daughter.

A patient prepares for surgery. Blood is drawn, vital signs are checked, and lab work is completed. Now there is only to wait for the moment they will be wheeled into the operating room. Bright white lights exposing their abdomen, doctors working quickly and efficiently to remove one of their kidneys; not because they have suffered a trauma or because of an illness, but instead to save the life of another. Through a kidney paired donation an individual chooses to donate their kidney which will remarkably not go to a loved one, but to a complete stranger.

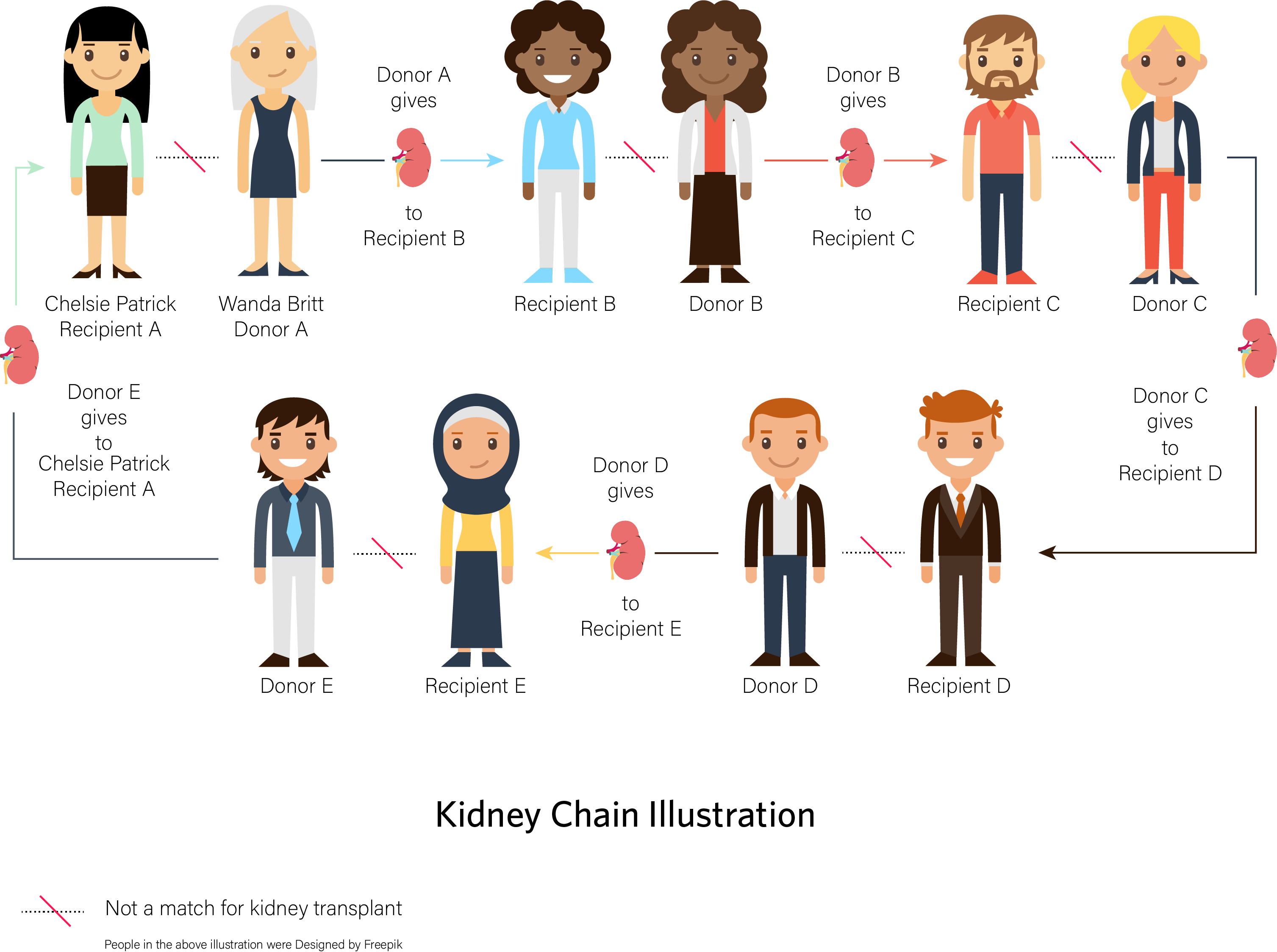

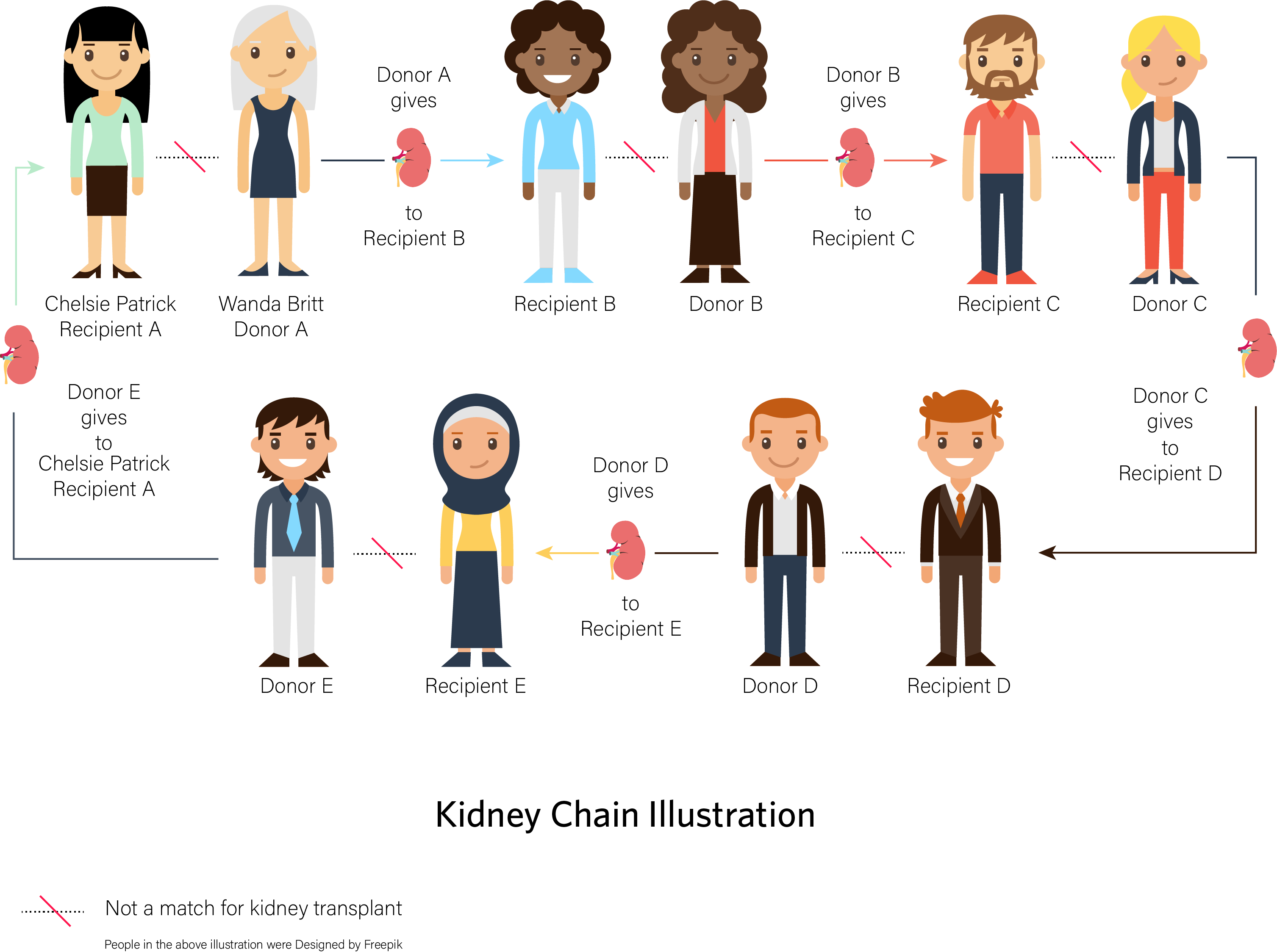

The surgery is the beginning of what’s called a kidney chain, an interconnecting, linked chain of individuals in need of a kidney transplant. It begins with a person in need, Recipient A, and a person who wants to donate a kidney to them; maybe a loved one or friend but who has been deemed an incompatible donor. That donor is referred to as Donor A. The chain then stretches across states, time zones and thousands of miles as the first donor completes their surgery and kick starts a domino effect that takes hundreds of hours to organize and bring to fruition.

There are approximately 100,000 people on the deceased donor kidney transplant waitlist, many of whom wait 5 to 10 years before their name is called to receive a kidney. 5,000 people die each year waiting for a transplant while another 5,000 are removed from the list because they are no longer healthy enough to receive a transplant. So what are the alternatives?

Chelsie Patrick was diagnosed with Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis also known as FSGS at 12-years-old. The disease caused scaring of her kidney, eventually leading to enough damage that affected her kidney’s ability to function. After being diagnosed, Chelsie was informed that she would need a kidney transplant one day. She remained stable until 2012; but after her son was born her kidneys began to decline, causing her to go into renal failure and forcing her onto dialysis. She was placed on the deceased donor waitlist in 2014

Every night Chelsie would go through her nightly routine of getting ready for bed, but unlike many people, her routine was very different; ending her evening by hooking herself up to a peritoneal dialysis machine. For 9 hours as she slept, she received her dialysis treatment. “My son would call it my cord,” says Chelsie. “It was very inconvenient, but it helped me have the energy I needed to take care of myself and my family. I wasn’t as lethargic or taking naps for hours every day.”

Relatives were tested immediately to see if someone was a match to donate a kidney to Chelsie, but the search was unsuccessful. Her mother, Wanda Britt, stepped forward wanting to donate but her blood type was incompatible. The doctors at the University of North Carolina Jason Ray Transplant Center thought that it could still work with the help of anti-rejection medication administered in advance of the surgery. A date was set for June 2015, but things did not go as planned. “The day before the surgery, Chelsie had a bad reaction to one of the medications we gave her,” says Amy Woodard, Living Donor Coordinator at the UNC Center for Transplant Care. “Because her mother was not the right blood type and the blood type incompatible protocol didn’t work for her, she was presented with the only other option, the kidney paired donation program.”

Kidney paired donation is the exchange of kidneys from living donors who are deemed incompatible with their intended recipients. The UNC Center for Transplant Care registered Chelsie as a recipient and her mother Wanda as a donor to the National Kidney registry list. The National Kidney Registry (NKR) is a nonprofit that helps facilitate living donor kidney donations around the country, building complex chains of kidney swaps by matching compatible donors with patients needing a transplant. Since they started in 2007, they have helped facilitate over 2800 kidney transplants.

In early December the UNC Transplant team was contacted by NKR letting them know matches had been identified. The hospital responded within the 24-hour time frame, and the process moved forward into the logistical and planning phase.

“In seven years of doing this NKR has facilitated a couple thousand of these, so they have the process down,” says Dr. David Gerber, Director of the UNC Center for Transplant Care. “They manage the logistics, who is going into surgery, what is going to be used for transport to get a kidney from your site to the next site, they help with all of the coordination. It’s like FedEx on steroids for health care. It has made a difference in our transplant center, and it’s an option we educate all of our recipients and donors about during their patient orientation class.”

After the details were worked out, the transplant team reached out to Chelsie and Wanda to schedule the surgeries. “When they called me and told me there was a compatible match, and I would be getting a kidney I was very excited,” says Chelsie, “but also hesitant. I had come right up to the surgery day before, and it had fallen through, so I didn’t want to get my hopes up too high.”

On October 24, 2017, each donor and recipient was in place, and the logistics all worked out. Wanda would start the chain, giving up her kidney to a recipient in a hospital in another state so her daughter could receive one within the next 24 hours. However, there was an unexpected issue that arose the day of the surgery. “The morning of my surgery,” says Wanda, “they took my blood to check my vitals. Soon after, the doctor came in and told me that we had to cancel my surgery because I was severely anemic and my hemoglobin levels were very low. I was devastated, all I could think was that my baby girl wasn’t going to get her kidney and she was going to be disappointed yet again. I dreaded making that phone call to her.”

The Surgical team along with Wanda’s advocate and health care champion Dr. Karin True, Assistant Professor of Medicine in the division of Nephrology and Hypertension at the UNC Kidney Center felt that it was not in Wanda’s best interest to move forward. They instead decided to spend the time to figure out why she was so anemic and how they can correct it. However, hope was not lost.

“We did not operate on Wanda that morning,” says Amy Woodard, “which means the person she was donating to at the outside hospital didn’t receive her kidney. However, this person’s donor had already made plans to donate and was comfortable going ahead and donating before his recipient got a kidney. We were confident that once the anemia issue was resolved, Wanda would return to donate her kidney to that intended recipient.”

So, in the end, Wanda was not the first donor in the kidney chain, but the last. The rest of the surgeries continued on that day allowing Chelsie to receive her kidney on October 25th. Wanda then became what’s referred to as a bridge donor, meaning she would donate her kidney at a later time. Over the next few months, as Chelsie got stronger and recovered from surgery, Wanda regularly came back to the UNC Center for Transplant Care to receive iron infusions. Finally, on December 12th Wanda donated her kidney to the intended recipient.

“The team of doctors, nurses and staff were wonderful,” says Wanda. “Everyone was so caring and kind. On my last follow-up visit after the surgery, I told them all ‘I love you guys, you’ve done a fabulous job, but I’m glad I don’t have to see you again.’ The paired Kidney donation is amazing. Everyone I’ve told about it is so surprised because they’ve never heard about it. I wish more people knew about the program so more lives could be saved.”