Urinary tract infections are common, regardless of practice setting or medical specialty. The management of UTIs has progressed significantly in recent years due to shifts in antimicrobial resistance patterns and additional evidence to support optimal diagnosis, antibiotic selection, and antibiotic duration.

The Carolina Antimicrobial Stewardship Program’s incorporated local microbiological data and evidence-based updates to best care for our patients in its updated UTI Guideline. To accomplish this goal, CASP collaborated with a multidisciplinary group of physicians and pharmacists.

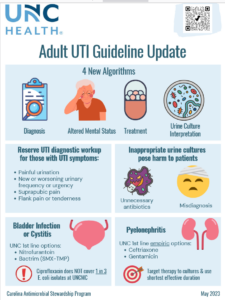

Diagnosis of UTI, in patients that can report symptoms requires the presence of UTI-specific symptoms. These symptoms may include dysuria, suprapubic pain, flank pain, or tenderness. If no UTI-specific symptoms are present, then the diagnosis of UTI can be excluded, and the patient should not receive a UTI diagnostic workup.

Based on local UNC data, one in three E. coli UTIs are resistant to ciprofloxacin. For cystitis, nitrofurantoin and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim are now the recommended treatment options.

While this approach is straightforward in patients capable of reporting symptoms, it can be much more challenging in those who cannot report symptoms. The updated guideline provides a new algorithmic approach to assessing patients with altered mental status or delirium. This algorithm incorporates evidence-based delirium screening tools, patient-specific factors to guide diagnostic workup, and alternative diagnostic considerations if UTI workup is inappropriate.

Treatment recommendations reflect the shifting resistance patterns of common urinary pathogens, such as E. coli. While fluoroquinolones were historically used to treat UTIs with good clinical outcomes, there has been an increase in rates of fluoroquinolone-resistant E. coli. Based on local UNC data, one in three E. coli UTIs are resistant to ciprofloxacin. For cystitis, nitrofurantoin and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim are the recommended treatment options due to their broad coverage of the most common UTI pathogens, extensive clinical data, and more favorable adverse effect profiles. For pyelonephritis, ceftriaxone remains a first-line treatment option. The UTI Workgroup newly recommends gentamicin once daily for pyelonephritis. Gentamicin has excellent coverage of common UTI pathogens, even in patients with risk factors for resistant isolates like ESBL or carbapenem-resistant E. coli, and achieves high urinary concentrations. Similar to prior recommendations, these therapies should be targeted to treat patient-specific urine cultures (if obtained and treatment is indicated).

The shortest effective treatment duration should be used for patients with UTI, to minimize antibiotic-related side effects and the development of resistance. Treatment duration largely depends on the antibiotic used, urologic anatomy/function, and site/severity of UTI (cystitis vs. pyelonephritis and presence of bacteremia).

The use of oral antibiotics is typically appropriate for patients with cystitis. Patients with pyelonephritis can also transition to oral therapy, pending clinical stability and urine culture susceptibility data. In recent years, there has been a growing body of evidence to support the use of oral antibiotics for patients with gram-negative bacteremia secondary to a UTI. The updated guideline provides patient-specific criteria to help guide this approach and recommendations for appropriate oral antibiotic options.

The updated UTI Guideline is now available on the CASP website. If you would like to get involved in future CASP guideline development, please contact a CASP team member.

Nicholas Kane, PharmD is a PGY2 pharmacy resident with the Carolina Antimicrobial Stewardship Program at UNC Medical Center.