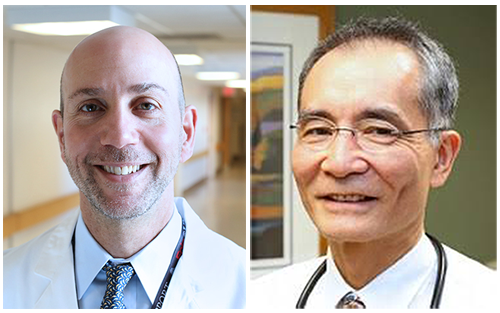

Ron Falk: Hello, and welcome to the Chair’s Corner from the Department of Medicine at the University of North Carolina. This is our series for patients focused on organ transplant, and today we will talk about liver transplant. We welcome Dr. David Gerber who is a Professor of Surgery in the Department of Surgery, and he is the Chief of Abdominal Transplant Surgery. We also welcome Dr. Skip Hayashi who is an Associate Professor of Medicine in our Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and he is the Medical Director of the Liver Transplant program at UNC. Welcome, Dr. Gerber and Dr. Hayashi.

David Gerber, MD & Skip Hayashi, MD, MPH: Thank you.

Cirrhosis and Transplant Evaluation

Falk: Let’s start this conversation with an understanding for a patient what you do. What do you, Skip, do as a hepatologist, and what do you, David, do as the liver surgeon? How should a patient think of your various roles?

Hayashi: These often are patients referred to us who have signs of liver failure, often cirrhosis. My job is to meet them, assess them—first of all to make sure they’re stable and get them stabilized, then quickly decide two questions. Basically, it comes down to one: Do they need a liver transplant evaluation, now or soon? And two: Are they an appropriate candidate? Not every person can withstand the rigors of a transplant. Then we take it from there. We will follow them for quite a while until the transplant, and then we pick them up several months after the transplant.

Falk: Why does a liver fail? What causes cirrhosis? Why would you want to do a transplant in the first place?

Hayashi: There’s sort of a long list of causes of cirrhosis. The more common ones these days—probably the most I see are non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, that’s associated with things like diabetes, high blood pressure, being overweight, and it can affect the liver to the point that they develop cirrhosis. There are other causes. People have heard of hepatitis C, hepatitis B, of course there’s alcohol. Other etiologies would be less common, and they break down to a lot of autoimmune diseases and genetic disorders.

Falk: What is cirrhosis?

Hayashi: It’s just advanced scarring of the liver. It does not necessarily mean that your liver is failing, but I like to say that you’re on the doorstep of failure and you need to be monitored.

Falk: If a liver scars, it means it can’t regenerate?

Hayashi: Not very well anymore, and that’s the problem. So, the liver gets to a point—it does regenerate very well, up to a point, but when it gets to a cirrhotic point it doesn’t do very well anymore.

Falk: So, the liver is trying to repair itself, regenerate, try to repair itself, regenerate, and then at some point it just ends up scarring.

Hayashi: Right, and then it creates other problems for the liver and eventually shows signs of failure. That’s when transplant certainly needs to be considered.

Falk: So, if Dr. Hayashi has seen this person already, Dr. Gerber, when as the surgeon do you get mixed into the fray?

Gerber: We work very much in tandem in transplant—the medical and surgical colleagues. Obviously, Skip and the hepatology team do their job in assessing the patient’s liver function, liver disease and progression, and the early assessment of if they would need a transplant. Now, to do a transplant means major surgery, so the surgical team comes in to do a surgical evaluation to complement the testing that’s been done. In simple words, I say this to the patient, to make sure they can get through the surgical procedure and have a good recovery.

Basics of the Liver Transplant Operation

Falk: Both of you have used the rigors of the transplant. What are you talking about?

Gerber: Folks with progressive disease of their liver, as he was talking about with cirrhosis, it comes to a point where that organ is no longer going to work functionally for you, and would end up leading to an early mortality or early failure of life. Replacing the organ, something now which is part of our mainstream health care is what we talk about with transplant, it’s just that—it’s removing your entire diseased liver, and replacing it with a healthy liver from either a deceased donor or a living donor, and there are some complexities to both of those.

Falk: That operation can take a while.

Gerber: It’s a big operation. It takes several hours—on average, probably six to eight hours. It’s a procedure now we’ve been doing since the early 1980’s, and roughly 7,000-7,500 patients a year in the United States undergo liver transplantation.

Falk: In the world of kidney transplant, the kidneys stay in, but in liver transplant, the liver comes out. Is that because of space, or is that because of how you hook the organ up to blood supply?

Gerber: You bring up a great point and we talk about this with our patients. In kidney transplant, we leave the old kidneys in place, because typically, as you know as a nephrologist, those kidneys have scarred down and they’re all the way down in the back, and the kidney gets put into a different anatomical location—it’s called “heterotopic transplant.” In liver, we actually remove the diseased liver for two reasons: one, you brought up, which is the blood supply. The blood supply of the entire intestines goes through the liver, and we need that blood supply to go through the healthy liver so the liver can do its metabolic and detoxification functions.

The other reason we remove that diseased liver is that chronically scarred liver is certainly at risk for developing liver cancers and we would be continuing to survey that liver, and say if we had left that liver behind, that would make it very difficult to manage the disease.

Falk: The liver goes into its normal spot, it’s hooked up to the blood supply, and it’s ready to roll.

Gerber: That’s right, it’s like replacing parts in an engine—you’ve got to put them back where you took them out.

Waiting for a Liver & MELD Score

Falk: So how long does somebody wait for a liver on the list? Let’s say it’s a deceased donor liver. What do you tell patients?

Hayashi: Yes, for quite a while now—almost a decade now, fifteen years now, it’s now sickest first. Unlike other wait lists, on other organ wait lists time on the list matters—liver, not so much. It’s really sickest first, and what I tell patients is if you’re not that sick, you could still sit on the list for literally years. On the other hand, if you get sicker, your priority then will go up, and you can get a transplant within a matter of weeks, depending on how sick you actually get.

Falk: How do you measure how sick somebody is? There’s a score that you use.

Hayashi: That’s correct. Right now, it’s called the MELD sodium score. It’s based on four values, this was done to make it an objective and fair way to prioritize patients on the list. These four lab values are actually plugged into an equation. I tell patients they can do this themselves on the computer if they’d like—they can Google it and find it. MELD scores range from 6 to 40—they’re whole numbers.

Falk: The higher, the worst.

Hayashi: That’s right. If you have a MELD of 40, you’re going to need a liver pretty darn quick and if you stay there for a week or two you’re in trouble. A MELD of 6 is normal. Right around a MELD of 15, 17, 18, in general, we start thinking about, Hey, you ought to be thought about for a transplant.

Falk: These are blood tests, a simple blood test that has to do a liver function test, serum sodium as well.

Hayashi: And the serum creatinine function.

Falk: And they’re all mixed in together with an algorithm so you can calculate the score.

Hayashi: Correct. If they have these lab values, they’re standard blood tests. They don’t need to special order any.

Falk: Let’s name them.

Hayashi: Serum sodium, creatinine, bilirubin, and the INR which is a measure of how well your blood clots, and those are all standard blood tests anyone can order in a primary care office.

Falk: In a world of electronic medical records, if one got those four values, which the patient would end up being able to see, they could plug them into this calculator and understand how that MELD score and their degree of sickness and potentially their position on the list?

Hayashi: They can, of course there are a lot of caveats with that. For example, the big one is if the patient happens to be on Coumadin, which is a blood thinner, that will artificially raise your INR. Therefore, that does not reflect necessarily your liver function or dysfunction. Things like that, but yes, in general it will give you a ballpark idea.

Sources of Liver Organs

Falk: Where is the liver coming from, Dr. Gerber?

Gerber: The patient always asks, “Well, where am I on the list?” This leads to your question of, “Where does the liver come from?” Each center has a list of their patients but the list that patients are always asking about is a virtual list that gets generated when there’s a deceased donor. Currently, livers are allocated in a model that takes out the most sick patients, as Dr. Hayashi pointed out, those high MELDs—36 up to 40, or people in fulminant liver failure. It allocates those livers into one of 11 regions that go across the United States. In North Carolina, we’re in Region 11—we share that region with South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky, and a little snippet of West Virginia—that’s our region. If you had a MELD or a loved one had a MELD of 40, and there was a donor anywhere in that region, you would likely be the first person on the list—assuming there isn’t somebody else with a higher MELD score. If there’s nobody that’s that sick, then the livers are allocated to what’s called a local model. In North Carolina, there are two local districts—we’re in 1—that covers from Winston Salem, draw a line south and it goes all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. Then there’s another local area that would be to the west side of that line.

Falk: As a patient, then, don’t you want to be listed in multiple spots to increase your chance of getting a liver without ending up being extremely sick?

Gerber: That’s a great question, and a conversation that we have with patients, and maybe I’ll let Dr. Hayashi carry that forward.

Hayashi: You’re right, and you just have to understand what David said about where these local regions are. You obviously don’t want to be listed in the same local region, that doesn’t do you much good, but if you want multiple listings, and patients do ask about this—if they have the ability to get to another center that’s outside of our local region, we often will let them know that that they can do that and we often do recommend it.

Falk: What do you do with folks who are not super sick who have substantial liver disease, who are symptomatic from their liver disease, who have swelling in their abdomen, swelling in their legs, who are a little bit yellow, but whose MELD score is 18, 19, 20—not high enough to get an organ in one area but the person’s quality of life is not what they want? Would that person benefit from being listed in all sorts of places?

Hayashi: Sure, and obviously that brings up a lot of other issues—socioeconomic, how capable are they to get to regions afar, there’s going to be out of pocket costs, travel expenses and things like that. The other thing that I talk to all of my patients about, especially this group, is the kind of organ they are willing to consider. I like to say that getting a liver is not getting a new liver—it’s almost like getting a used car in a way, it’s been used by someone else. Just like when you go to a used car lot, there are a variety of used cars, and just like this liver, there are a variety of qualities to those organs. These organs—some of them, may have what I like to say, just some little issue with them, and are fine organs but they are expanded criteria donor liver.

Falk: How do you decide? You have a patient sitting there, they need a liver. How do you decide whether that liver really is a good liver?

Gerber: First off, anticipate the needs of the patient, as Skip just said. Those patients who are sicker and maybe their MELD score isn’t capturing it, we want to make sure that we’ve looked at every liver potential for them. Going back to your question—how do we know if that’s a good liver? It is a little crystal ball-like, every liver is used to some degree, and there are many variables with how the liver will function. We look at what the donor has gone through prior to brain death, if it’s a brain-dead donor, and make an assessment based on what we know with how that donor matches up against other donors across the country. There are a series of metrics that we can use. They’re never perfect, but they can get you into a ballpark category.

Falk: Some centers do living liver transplants, others don’t. How does a living liver transplant work?

Gerber: In that case, as with any major surgery, you have to have a program established with expertise and focus in living liver donation. It’s a technically challenging operation, but for people with expertise, it’s doable. There are risks involved to the donor, much as there are in living kidney donation. In living kidney donation, we talk about the major risks of being roughly 1 in a 1,000—that includes death and major complications. In the liver field the current number is closer to 1 in 300 to 1 in 400. It’s obviously a more palpable number.

Centers that do living liver donation or living liver transplants, typically are looking at the balance between their deceased liver pool and the needs of their patients. There is sort of this balance that you want to achieve, because you want to do enough of them per year to keep the machine efficient and optimized, it helps to give the patients the greatest benefit. There are some regions in the country that have put more effort into that and have very active programs.

The other area where living liver donation comes into play is when you’re looking at a small recipient, in the case of a child. That’s where living liver donor transplant started. If you look at an infant, two, three years old, or younger, they can often times match up suitably from a volume standpoint with one third or one quarter of an adult’s liver. When you look at the liver, it’s not a rectangular box, it’s segmented. We can remove two of those segments intact, together, and use that as the graft for the pediatric recipient. That meets a need that is truly unmet in the deceased donor pool, because there are very few pediatric deceased donors. When you look at living liver transplant, the ratio is weighted significantly towards pediatric recipients, typically from a parent.

Falk: If you’re a parent and you have a sick child, no question.

Length of Wait and Recovery Times

Falk: Skip, what other questions do patients ask you as they are put on the list? What are common questions?

Hayashi: Well, we already touched on one, “How long will I wait?” is one of the most common. I tell them what I just said, a lot of it depends on how sick they are and where their MELD score is. Then the next question they want to know, and I defer them to David, they want to know, “How long am I going to be in the hospital? What’s my recovery time? How long will it be? When can I get back on my feet and get back to work?” Those are the questions I get most often.

Falk: So, David, how long are they going to be in the hospital? And when do they get back on their feet? And they started out pretty ill to start with.

Gerber: Exactly, and we have to factor that in, and as we know in medicine, we always speak in averages when we wear long white coats. It’s always hard to predict for each individual patient, but we give them the reference point to say the average length of stay in the hospital is roughly ten days. That’s usually two days in the ICU, eight days on the floor before they’re ready to be discharged. But you bring up a very good point—the very sick, malnourished, deconditioned patient is unlikely to be here for ten days. They have more hurdles to get to, to make that recovery so they can be independent in their functions outside of the hospital. Those people do tend to be here a little bit longer.

When I talk to patients about recovery, and this is almost independent of how ill they were—I tell them it’s a six-month recovery, because remember transplant is one part, the major operation, and second part, reconditioning from how sick you were, and the third part is all these medications you have to take to prevent what’s called rejection, where your body tries to attack the organ. As we know, medicines have side effects and side effects kind of build on top of one another, so it takes a while before patients really feel themselves.

Falk: Let’s go back to that living donor question. How long do you tell a living donor parent they’re going to be in the hospital and can then take care of their child?

Gerber: Right. Undergoing major surgery like that, they’re going to be in the hospital—if it’s the small part of the liver, they average around five to seven days in the hospital. If you’re doing a donation where an adult donates almost half their liver to another adult, they’re likely to be in the hospital closer to two weeks because it’s a bigger operation. Again, as we follow them through that progression.

The key part of that question is taking care of their child. They are in no physical condition to take care of their child two weeks after major surgery, so essentially, we’ve now created two patients. A lot of what we do in the transplant evaluation is looking at that social structure and infrastructure of support, what it would look like for the patient or patients, to make sure that’s going to be in place for the next six weeks or longer in the case of a living donor until they both have recovered.

Falk: Once you have transplanted a patient, how long do they end up seeing you? Is this a lifelong commitment, or is this a relatively short one?

Hayashi: I always tell them this is a life-changing event. They will forever be seen and connected with us. If they move out of the area, we will try to get them connected with a new transplant center. Granted, as the years go on, we hope they will only be seen annually but they shoul not think that they’re going to leave the realm of the transplant center.

Gerber: Anecdotally, they really do look at this as an unbreakable bond. I personally have two patients who have followed me, one who just moved to North Carolina who I transplanted 23 years ago—she had been with the team when I was in my training, and another was a pediatric patient who I transplanted around 25 years ago who we’ve been following. They really do develop quite a bond with the transplant programs, it’s a very unique bond and a great opportunity for our trainees to see longitudinal care delivered in that way.

Outside Activities that Influence Dr. Hayashi and Dr. Gerber

Falk: Skip, you are an avid fly-fisher person. What has fly fishing taught you about liver transplantation? Or what has liver transplantation taught you about fly fishing?

Hayashi: I actually go fly fishing to get away from my work a bit! Well, for one thing, if anyone is listening who’s a fly fisherman, if there’s one thing it teaches you it teaches you patience. It teaches you patience, and it teaches you to be somewhat meticulous. It teaches you how to concentrate. When you’re working a fish—Dr. Falk knows, he’s a fisherman too—

Falk: A very bad one.

Hayashi: I have been known to be so focused on a fish that I didn’t see a grizzly bear coming up on me when I was fishing in Alaska. You get very focused and you’re paying attention to every little detail.

Falk: Dr. Gerber, you also have another career in the military. How has your military experience influenced how you think about liver transplantation or transplantation in general, since you also take care of kidney patients?

Gerber: Great question, but not nearly as exciting as the fly fishing question! Clearly, I’m more boring than Skip! The military experience has certainly given me an opportunity to look at other large systems and how they run and the analytical thinking that goes into decisions. Obviously, I’m not out there fighting wars on the front line, but I get to read a lot about that, and the thought processes that are involved in running large programs with multiple individuals, multiple personalities, getting alignment, consensus, are things that I’ve definitely learned in the military, and have hopefully been able to apply here at UNC.

Falk: What is really clear talking with the two of you is that this is really a team. It’s a team more than just in words, it’s a team of individuals who absolutely interact, can kid around with each other, but are focused on making sure the patient gets through this experience unscathed.

Hayashi: That’s partly why I’m in this field. I’ve always been better when I’m around other people who are focused and passionate about what they’re doing as a team. For example, here, what’s been nice, is for a couple of hepatologists, we share space in the clinic. I think that’s true of a lot of transplant program centers, we have a single clinic. It’s great, we get to interact and bump into each other, and we get to see our patients, before and after transplant.

Falk: So, as a patient, you are really seeing a team that is localized together, works together, and can kid each other all at the same time.

Gerber: It’s one of the great things about transplant, we teach residents and students, that most of medicine you can function in a silo, but transplant is so multidisciplinary in its nature—kidney transplant is much the same way. It’s great to have joint clinics, because we get to see patients at different stages.

Additional Sources of Information

Falk: Where would you suggest patients look for additional information? Is there a reasonably accurate source of information?

Hayashi:On the pre-side, before you get a transplant, if you have a liver disease or cirrhosis, there is the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, which is our major US liver organization for physicians and health care providers. Then there’s something called the American Liver Foundation, which is also a great source of information, so I usually point people there.

Falk: Thank you, Dr. Gerber and Dr. Hayashi.

Hayashi: Thank you for having us.

Gerber: Thank you, Dr. Falk.

Falk: Thanks so much to our listeners for tuning in. If you enjoy this series, you can subscribe to the Chair’s Corner on iTunes or like the UNC Department of Medicine on FaceBook. Thanks so much.

Visit these sites for more information: