Andy Nelson is a person who has idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and received a double lung transplant. He shares his story here as part of our series, “Understanding Organ Transplant.” Andy talks about the progression of his illness, his journey to getting new lungs, and his recovery since the transplant.

“I progressed very rapidly. I’ve gone through some serious events in that process. Yes, it is painful, but there is hope in every moment. Life has meaning and is purposeful even in those moments.”

– Andy Nelson

Ron Falk: Hello, and welcome to the Chair’s Corner from the Department of Medicine at the University of North Carolina. This is our series for patients focused on organ transplant. Today we will get to hear from a person who has had a lung transplant, Andy Nelson.

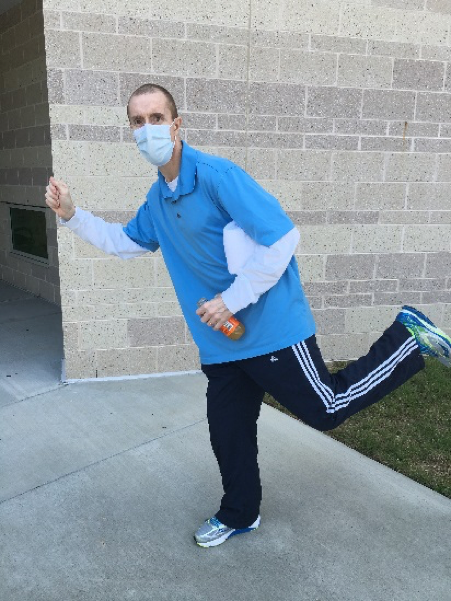

Andy’s story is relatively recent with respect to his transplantation. He received a lung transplant a little over a year ago, in 2016. He is also a UNC employee, so some of us have known him as a colleague for some time, and some have helped in his care as a patient. Today I will get to ask Andy about getting sick, what it was like waiting for new lungs, and what his recovery has been like—and I can tell you I’ve seen Andy in the gym, so I know that to a certain extent his recovery is going well. Welcome, Andy.

Nelson: Thank you, Dr. Falk. It’s good to be here.

Early Signs of Illness

Falk: Let’s start by telling us who you are and what was your life like before you even thought about a lung transplant.

Nelson: After graduating from college at Clemson University in finance and accounting, also picked up a CPA license in North and South Carolina—I started my career in health care. I worked in health systems, corporate accounting, corporate finance. I also worked in strategic planning business development for a number of health systems. Prior coming to UNC in 2007 I was working at the University of Kentucky Health Care.

My wife and I have been married for 23 years, we have 4 daughters, Throughout my 20-year career, I’ve never had a sick day. I’ve been healthy and fit my entire adult life. I’ve been committed to that, exercising and eating healthy. Never smoked. Our family was very active and healthy. In terms of health encounters, I really had no encounters other than my professional life. I looked at health care through the lens of data and new patients, but it was foreign for me to even think about being sick. If you move all the way up to 2013, I had no sign or symptom of anything and had not been to a doctor in many years, and didn’t have a primary care physician at the time.

Falk: And then “boom.”

Nelson: Yes, well, the boom was more subtle. For me, my first remembrance of an issue was a subtle cough that didn’t seem to go away, it was dry. The onset was sort of an incessant cough, I can’t even remember the specific date of when it got bad enough for me to notice, but my wife and daughters noticed it. I said, “It’s probably just allergies.” This is in mid-late 2013. My wife and daughters said, “You need to go see a doctor,” and I said, “I’m fine.” It wasn’t affecting my workouts, it wasn’t affecting my work at the time—I could take some cough suppressants and get through the day or get through a meeting or presentations, so in December of 2013 that’s when I started waking up my wife coughing, and that’s when she said, “Enough’s enough, you need to see somebody.” There started the hunt for a primary care physician. I went to see one of our primary care physicians at UNC. I didn’t know what I was getting into. He asked me, “When’s the last time you have seen a physician?” and I said, “Well…it’s been quite a while.”

He gave me the surprise of the full Monty, the full physical exam, as he assessed me he said it was probably just allergies, so we started with allergy medication. I tried allergy medication for about a month and said, “This isn’t helping at all.” I’m still having to take cough medicine, I’m coughing now throughout the day, no shortness of breath and not affecting me in any other way. He said, “You might have adult-onset asthma.” We actually tried some inhalers at that point. That didn’t help relieve anything either. He began to get suspect. This is really where I value the role of the primary care physician and doing his due diligence. He did an in-office spirometry breathing test to see how my lung function was, and by this point I could tell I might have lost a little bit in the gym, but I attributed it to my geriatric phase of life, moving into an older phase.

Falk: How old are you?

Nelson: I’m 47 years old.

Falk: So, geriatric—at the age of 44 or 45, that doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Nelson: I thought I was aging in dog years at that point, plus having new kids at home, lack of sleep and so forth. He does the spirometry test and says, “Andy, it looks like you’ve lost some lung function,” maybe down to 90 percent, 80 percent, “I’m going to send you in for a chest x-ray.” Right after the chest x-ray, within an hour he calls, and says, “Andy you’ve got some scarring it looks like around your alveolar tissue, or tissue in the lungs. It looks like you probably have an interstitial lung disease.” He went on to explain that this is a broad spectrum of lung diseases—over 200.

Falk: How quickly did you, in your health care role, quickly start Googling that?

Nelson: Yes, that is a part of my professional life is triaging clinical cohorts and understanding them. So, you as a physician, if you give me a diagnosis or a procedure it’s up to understand the nuances and mechanisms, so I started reading a lot about interstitial lung disease. I knew it was a broad spectrum. Since my only symptom was a dry cough, it’s not that I was in denial, I thought, “Well I could have this the rest of my life and be okay.” At this point is when I go to see a specialist. Dr. Lobo put me through a lot of tests, in-chamber pulmonary function tests. Ultimately, I went to get a high-resolution CT scan. That was enough to confirm a diagnosis. I distinctly remember him mentioning the words idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. I’m not a Latin scholar, but I know enough to know that idiopathic didn’t sound good to me. I could piece together the other parts.

Reacting to the Diagnosis

Falk: “Idiopathic” is used a lot. Idiopathic means we don’t know the cause. The medical community does not recognize in an individual person what the underlying cause or mechanism of disease is. In your case, pulmonary=lung, fibrosis=scarring. Scarring of the lung for uncertain cause. What happens when you as a patient are given that word, “idiopathic?” What emotions run through you?

Nelson: For so long I had been outside the snow globe of patient care, I had not been a patient. I remember when he mentioned that, unlike the diagnosis of an interstitial lung disease, this was a more serious conversation where he said, “Andy, this disease is progressive, it’s terminal, and there’s no cause and no cure.” I asked him what kind of timelines are we talking about? The average post-diagnosis survival rate for a person diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is three to five years. Dr. Lobo qualified that by saying that the majority of people are diagnosed older than me and often caught later in the diagnosis. Since I didn’t have comorbid conditions, or other health issues, that I could have this disease for a long time and even though there isn’t a treatment, potentially there could be one. I had some mixed emotions, probably some denial that was baked into that. I was trying to be as practical as I could, but the only symptom I had at the time was a dry cough.

Falk: You could have all the CT scans in the world, but at the end of the day, if you’re feeling okay and can go about your activities of daily living, except for a cough and maybe being a little short of breath in the gym, it’s hard to come to grips with those words, “I’m in trouble,” when I feel so well.

Nelson: That’s right. One of the emotional obstacles or issues that arose as I drove home to talk to my wife and my daughters, who at the time were 15, 12, 4, and 2. Here’s my wife, and I’m having to prequalify my statement by saying that, “I’m going to tell you about a diagnosis but I may not fit the standard category. I may have this for a long time.” I knew my wife would do the same thing—she would Google it immediately. I tried to be measured in my words to her. I remember telling her, and there was the visceral shock. I could tell where her mind was going, “What can be done? And what do you mean there’s no cause for this? But you only have a cough.” My daughters, the older two old enough to understand that the runway may not be long for their dad. We went through a long process.

We have a strong family. When people talk about healing, you can’t understate the network of support the patient may or may not have at home. I was very fortunate. When we were going through the trauma of the diagnosis, it drew us closer as a family.

Getting Through Uncertain Times

Falk: What advice would you give to somebody who’s listening who is perhaps feeling worse than what you were, maybe is short of breath, doesn’t know if things are going to get better, but you know that they probably won’t? What do you tell them with respect with how to get through those emotions of all the uncertainty that you just described?

Nelson: We all have components, a spiritual, an emotional, a physical component. When I think about how we and I coped during this season, perspective was critical. Bathing in this reality, I was aware of my mortality, certainly. We all are to some degree. We all could say, tomorrow may be our last. But to be viscerally aware of that. To have meaning and purpose and hope in every moment. I didn’t see pain and suffering as meaningless; I see them as meaningful in my experience. I would tell people, “I’m on 8 liters of oxygen a day, 24 hours a day,” I was either going to suffocate or go into cardiac arrest. There were many days that I laid on the floor and could not catch my breath once the disease progressed.

For people listening, I progressed very rapidly. I’ve gone through some serious events in that process. Yes, it is painful, but there is hope in every moment. The hope is that life has meaning and purposeful even in those moments.

People going through this disease, you’re not alone. It’s good to get sounding boards out there, people who have walked it to some degree. Everybody’s story is very different and I’ve found all of us are very different and different stages of life and processing things differently. Ubiquitously, there’s a transcending component that says life has meaning and purpose. That gives us the ability to look and appreciate this next breath. Not to focus on the, “Why me?” but “What can I do with right now?” The disease helped me to deeply appreciate the moment. I had heard many people talking about being present and mindful—what does that mean? Nothing educates us quite so well as a shock. For me, the shock of the disease and being in the moment as a patient, you really get a sense of appreciating that.

You can easily spiral into self-pity if you’re not careful—“Why is this happening to me?” Especially when there’s no cause. My expectations were not high. I’m a human, and I realize that I live in this mortal frame and yet my hope was very high. Whether I got one more breath, or one more year, or one more decade, I was going to prayerfully hope for the best and seek to invest those moments well. Adversity teaches us a lot. Most people I know in life would say that. This was a teacher for me and will be a teacher for those in life who can maintain that perspective.

Finances & Transplant

Falk: You have this long and remarkable expertise in understanding finances. There are two financial components of what you’ve been through. One, is, “Oh my goodness, I’m the financial breadwinner for a family of six.” And also, “I’m thinking I might have a lung transplant, how am I going to pay for it?” Let’s do the first one of these. How did you deal with the whole process of trying to work, then as your shortness of breath worsens, not being able to work—what recommendations would you give for how to wind their way through their understanding of some financial security for your family? Whether you were planning for it or not, in a relatively short amount of time, you couldn’t do the employment that you had?

Nelson: I can remember toward the end of 2015, being unable to walk across campuses and go to meetings. That’s when I went and talked with folks at work about potential opportunities to bridge with some project work so I could continue some employment. If I was still, I could work. Unfortunately, if you’re in a profession where you have to work with your hands or have to move around a lot, that will be impossible.

Falk: One has to be able to say to oneself, no matter how hard I push, this is not a mind issue, this is a body issue. As part of my employment, if physical activity is required, it’s not possible.

Nelson: It’s not. You will be in a right place to file for disability at that point. You will need to look at your options. If you had disability insurance in the past, you’ll want to talk to your insurance about that.

Falk: If you don’t have that insurance, this is when social security disability actually has a very right role.

Nelson: Yes, this is the right role for disability benefits and the stewardship of health care would say that. To enlighten people into IPF on a daily basis, if I stood up, with eight liters of oxygen, or more, if I would just stand up and walk slowly across the room, I would desaturate. Meaning, I wasn’t getting oxygen to my body and my heart rate would spike up to 140 or 150 and I would have to lie down, I couldn’t catch my breath. I took showers sitting down, I couldn’t breathe. It got so bad that I had cardiac issues.

From February 2016 to June, in that stint I deteriorated very rapidly. It was a long journey to be sick enough to be on the transplant list and not too sick to not be on there. With that context though, I was very fortunate that I could work right up to transplant, for me, the work that I do, I was still able to do the mental work. As long as I had a laptop and could sit still on the oxygen, I could work. That provided some sustenance.

When you’re talking about the economics of a transplant, even with insurance, all of the costs that went into my pre-care just with IPF, it’s a lot out of pocket expense. You’ll want to work with your insurance case manager if they have one. Once I got sick enough to be put on the transplant list, I was fortunate at UNC. Most transplant centers have a financial coordinator. They were able to unpack a lot of information and resources. Of course, you can get them from associations, such as UNOS, the United Network for Organ Sharing. The information is there. But in terms of managing the finances, it’s really contextualized by the insurance. If you have Medicare, you have to work with the social security office to know what coverage you do or do not have. If you have traditional Medicare, if you have one of the other plans, you’ll have to work with those companies to find out what the coverage is. They get very specific.

It almost is a full-time job to manage this. If my wife were here, she’s an accountant, she would say the same thing. It takes a lot of hours and effort just to manage the financial piece, even from an insurance side. There are options for fundraising you could have and there are some foundations that can help provide financial assistance too, but you’ll want to put all that time and effort into understanding what those options are.

Falk: A financial counselor comes with a transplant program, which is of help.

Hope with New Lungs

Falk: You had this period of really difficult several weeks of feeling okay, then not feeling okay, then finally getting the call that there were some lungs for you. What was that like, and what was that immediate post-transplant period like?

Nelson: I found out I was going to be put on the transplant list in late June of 2016. What we had heard, even in the support groups we had, was that you could have a number of dry runs. If you got a call for a lung transplant, it might not be a match. You may have to go home and wait. I remember getting the phone call on Saturday, July 2, 2016, with my family, probably around 5 or 6:00 at night. They said, “We have some lungs.” This was only eight days on the wait list, so I was not expecting a phone call that soon. I thought it would be several months. I knew that if this was indeed a match, and I do go into surgery, it’s a major surgery. I can remember the mixed emotions as my wife and I left to come to UNC. In one sense, we’re joyful and thankful for this, because it could mean extended life for me. On the other side, you don’t know if you’re going to come out of that major surgery. I remember coming in, getting worked up in the OR. You know they’re going to go in and open up your chest, there’s the prayerful hope that I’ll come out of this. I’m very fortunate and blessed and thankful that I did. There are some wonderful surgeons here at UNC providing that care. It takes an orchestra to take care of a patient in transplant.

When I woke up, in my first memorable moments after my transplant, I can say that that first breath was remarkable. I did not realize how sick I was until I took a breath with those new lungs. It was very different to be able to inhale that much. I had been so restricted for so long and did not realize it.

Recovering from Lung Transplant & Maintaining Health

Falk: After transplantation, tell us a little bit about the recovery. Walk us through that period of time.

Nelson: After transplant, I remember being coached well, that once you’re out of surgery you need to start moving as much as you can. Even with all the tubes, I looked like a cell tower full of IV fluids. On day 2 postop, I was walking. It’s 150 yards end to end. I measured my steps and would walk the unit, then the hallway, then I got up to a mile at a time. Then by the time I left, twelve days after having surgery, I was walking four miles a day in the hospital with a walker. After I left the hospital, I remember going home and feeling like I could rest, but I knew the best thing I could do at the time was to try to move. I would put on my mask and get on the treadmill and just walk. For the first three months, I was doing extremely well.

In October of 2016, I had a low-grade fever. It turns out I had a pulmonary embolism, a blood clot in the lungs. I had acute rejection of my lung transplant and a possible fungal infection. The orchestra played again—I had all the clinicians in and out of my room. I was in the hospital for a week. Then I was back in the hospital in February for another infection. An infection is one of the leading causes of death after a surgery.

After February and since February, I’ve been on a wonderful trajectory. I remember distinctly, Dr. Falk, about six months ago being at the UNC Wellness Center and you and I were talking. You asked me when I had received my transplant, and I had heard about a magic window of time when people start feeling better or feeling some semblance of normalcy. You looked at me, and the prophetic Falk, you just said one word—“October.” Here we are in October. As of last month, my lung capacity, is at 100 percent. My pulmonary function tests have been improving every month that I’m going in. I go in for lab tests consistently to dial in the medications. That’s another piece that most people will need to understand is that you’re a walking pharmacy and you’ll want to make sure you’re compliant with your meds. The side effects are probably the thing you’ll wrestle with the most.

Falk: How do you keep yourself healthy now? You look and you are remarkably healthy now.

Nelson: There are several factors to that. One is a bit cliché, but diet and exercise is fundamental. You want to be as healthy as you can with your diet and exercise as much as you can, cardiorespiratory exercise. The other side of this, especially with a lung transplant, lungs are the only organ that aren’t encapsulated. We breathe in, and you’re exposed a lot. My white blood cell count is immunosuppressed. Hygiene, a real sensitivity to keeping your hands clean, my wife and my daughters- that environment is clean. Not being overly exposed—you’re not wanting to be a hypochondriac and in fear of being outside. Just being sensitive, not going into large crowds and making sure that if anyone is sick to try to stay away.

Support for the Patient and the Caregiver

Falk: You talked very eloquently about what it was like to tell your wife that you had this potentially terminal disease called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. She’s lived through your whole period of time where you really had a struggle to take another breath, and now the transplant era. This whole experience just underlines the critical need of a caregiver, an advocate who is there with you. What advice would you give to the patient about the value and importance of making sure that your spouse is able to communicate?

Nelson: This is critically important for patients who are going through this, and you mentioned too, the most important concept for a partner, somebody who is supporting you through this. The role of caregiver and advocate was evolving for my wife. She had never been in a role like this, so it added tremendous stress as you can imagine, emotionally and physically, and also as a mom of four, and having to manage that as well.

As a patient, it’s hard to give the encouragement that the partner needs as a caregiver. The caregiver needs support. Whether this comes from other family or friends, faith or church, you can’t understate the value of the emotional support needed. It’s easy to get emotionally spent. This is a chronic condition, and then you have a transplant, and it’s chronic after. It’s the sustainability and finding ways to and allowing yourself to be cared for in this process. It’s easy to get isolated in this. We were very fortunate and blessed to have the family and friends we had. I could spend hours talking about all of the ways that our family and friends really rallied around us during this time. It’s a tremendous part of the care and healing and quality of life for the patient and family.

Falk: When we’ve had conversations with couples or pairs, and interviewed them, there are a lot of lessons that one learns. There are a cascade of emotions, of fear, that one is going to lose the patient. There’s anger, quite frankly. “Why is this happening to me? Why is this happening to us?” There’s guilt by even having that emotion. There’s exactly what you described of the need for caregiver care. Caregivers become exhausted, especially if they’re having to be wage earner, caregiver for the patient, and parent if you have children. The caregiver feels the need for care, and then guilty that they’re taking away care from the patient. Then there’s depression in trying to get through all of this. Having these conversations about all of these kinds of emotions—fear, guilt, anger, exhaustion, depression, are really important conversations to have as one goes through these phases.

Nelson: You bring up something—part of the orchestra of transplant care here for me was the psychiatric piece and working through this. Preparing us even before the transplant and after, for some of the things that we would face on that front. It’s good to have those sounding boards there, the third-party objective boards, through that process.

Importance of Kindness and Compassion in Health Care

Falk: What advice would you give to all of the physicians who took care of you who would make your experience better? You’ve been very complimentary. I’ve been a patient here too, and there are some things I’d really like physicians to do differently. Give me an example of the biggest thing you’d like them to hear.

Nelson: I’ve thought a lot about this. You can’t distance yourself from the professional life you live too.. As we talk about quality health care and patient experience, provider satisfaction, all of the aims we have in health care. I thought coming in to this experience as a patient that I would be quite rational. I was very wrong.

Falk: I don’t think anyone who is a patient and really ill is rational. You can’t cope that way.

Nelson: I thought, I’m not in the clinical sciences, but I have a deep appreciation for it, and I thought I would be data-driven and fact-based as a patient. Well, I wasn’t at all. I inferred quality of a physician, of a nurse primarily through two things. They’re stated often. I’m choosing this word very carefully. One is kindness, sincere kindness. If you as a physician, if kindness is present, then for me, you’re a great physician. It communicated a lot to me and my wife when we were there. The other one—we say “compassion.” If physicians can allow themselves to pause and walk down the hypothetical, and just compassionately feel what the patient is going through, and extend kindness. Competence was implicit to me, but I would watch nurses and doctors come into the room, and they might bring the stress of the day in the room with them. They wore it. I could tell and it was not a good experience for me when I went through that. I walked away and thought a lot about that. Kindness and compassion are a tremendous part of healing. When a patient is in an inpatient setting, having all of the uncertainty, and maybe lack of communications sometimes as a patient, not knowing what’s going to happen. Hearing that they’re coming in fifteen minutes but then it’s two hours.

Falk: For those of you listening you should know that Andy turned red when we started that conversation. It’s really a visceral response when caregivers somehow forget that the reason we went into healthcare was to deliver kind, compassionate, high quality care. Everybody talks about quality improvement. The quality that needs to be improved first are the qualities you described, kindness and compassion, that’s exactly right.

Falk: Thank you, Andy, for sharing your story with us.

Nelson: Thank you.

Falk: Thanks so much to our listeners for tuning in. In our next episode, we’ll discuss heart transplant with Dr. Patty Chang. If you enjoy this series, you can subscribe to the Chair’s Corner on iTunes or like the UNC Department of Medicine on FaceBook.

Visit these sites for more information:

// var audio; var playlist; var tracks; var current; init(); function init(){ current = 0; audio = $(‘audio’); playlist = $(‘#playlist’); tracks = playlist.find(‘li a’); len = tracks.length – 1; audio[0].volume = .90; playlist.find(‘a’).click(function(e){ e.preventDefault(); link = $(this); current = link.parent().index(); run(link, audio[0]); }); audio[0].addEventListener(‘ended’,function(e){ current++; if(current == len){ current = 0; link = playlist.find(‘a’)[0]; }else{ link = playlist.find(‘a’)[current]; } /* run($(link),audio[0]); stops from going to next track */ }); } function run(link, player){ player.src = link.attr(‘href’); par = link.parent(); par.addClass(‘active’).siblings().removeClass(‘active’); audio[0].load(); audio[0].play(); }