Following is a conversation with a faculty member who is a past-President of the American Heart Association (AHA) and who twice met with US Presidents in the Oval Office to discuss health matters. He is prominent in national and world health, and served as Chair of the World Heart and Stroke Forum and President of the World Heart Federation as well as Chair of the NHLBI Executive Committee for Guidelines to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease, and Chair of the ACC/AHA Committee on Cardiovascular Guidelines. Today, he inspires future generations with his reflections on life and career.

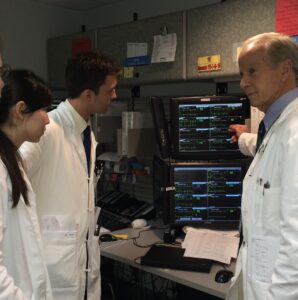

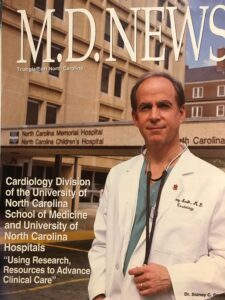

Sidney C. Smith, Jr., MD, former Chief of the Division of Cardiology has performed invasive procedures for more than 50 years in the catheterization lab (27 years at UNC Hospitals). As he looks to the future, he plans to increase his involvement with national and international quality improvement programs, while continuing to care for patients with cardiovascular disease and teaching UNC residents and fellows. In a recent interview, he reflected on his life, his accomplished career over the last 50 years and his dreams for the next 50 years.

You have been a major figure in the global organization of cardiology. Can you share some of your background and education? Did you always want to be a doctor?

I was born and raised in Wilmington, Delaware, strongly influenced by Virginia family roots. My mother and father were both from Virginia, my mother from Dinwiddie, and my father from Petersburg. Receiving undergraduate and graduate degrees in engineering from Virginia Tech, my father enjoyed a successful career with DuPont, headquartered in Wilmington, Delaware. My mother was an elementary school teacher until my brother and I arrived on the scene at which time she had her hands full and focused on the family. Growing up, I had no plans to be a doctor. In school, I enjoyed sports and science and pictured myself pursuing a career in engineering like my father. I followed his footsteps to Virginia Tech and majored in chemical engineering. However, there were several influential doctors in our neighborhood who had an impact on me, and after two years, I began to reconsider my choice of a career in chemical engineering. At the beginning of my junior year, following a summer student experience in Japan, I decided to pursue a career in medicine. With help from the Dean of Engineering I graduated with a dual major in Chemical Engineering and Pre-Med.

How did you decide on medical school? What came next?

When I was in my early 20’s and entering medical school, breakthroughs were occurring with artificial heart valves, transplants, and a variety of new diagnostic techniques were used to treat heart disease. These advances were a perfect fit for my undergraduate background in engineering, which was a true resource, especially in cardiovascular disease. I decided to attend Yale Medical School, which required a thesis, and shortly thereafter had the good fortune to be recruited to a summer research position at the NHLBI/NIH. There I met Dr. Robert Levy, NIH researcher and later Director of NHLBI, also from Yale, who spoke to the medical students working at NIH for the summer. I was asked to introduce him.

After his lecture we talked about my interests and his research work. Along with Dr. Don Fredrickson and Dr. Robert Lees, he was involved in groundbreaking research which ultimately resulted in much of our current understanding about the role of lipoproteins in cholesterol transport, their classification, and the development of cardiovascular disease. He invited me to work with him, which I did every summer during medical school. I wrote my thesis on lipoprotein abnormalities in primary biliary cirrhosis. It was absolute serendipity to have this opportunity!

What attracted you to cardiology and the cath lab? Where did you go from there? What was your first job?

I was accepted to a medical internship at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital at Harvard (now Brigham and Women’s Hospital), during which time I was recruited to a surgical residency with plans for a career in cardiac surgery. All of that changed when I met Dr. Richard Gorlin, then Brigham’s Chief of Cardiology, who encouraged me to join him for a cardiology fellowship focusing on cardiac catheterization.

He said, “if you like procedures, there’s a lot you can do in invasive cardiology,” and pointed to many other techniques evolving in non-invasive diagnosis and medical therapy. During my cardiology fellowship, I spent most of my time in the cardiac cath lab performing catheterization procedures, and focusing on research on coronary blood flow under Dr. Gorlin, and left ventricular mechanics (Vmax) with Dr. Ed Sonnenblick.

My cardiology fellowship was during the Vietnam era, and upon completion, was followed by two years in the Navy working in the cath lab and attending on the cardiology service at Portsmouth Naval Hospital (1300 beds). I followed legendary figures like Dr. Jess Peter and Dr. Doug Zipes, both graduates of the Duke Cardiology Program. This was a turbulent time with arguments about our involvement in the Vietnam conflict and assassinations of key leaders such as John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King. Later, I recall watching historical accounts on TV with my daughter when she was then 8 years old, after which she said, “Dad, you grew up in a violent period.” It’s hard to communicate what those days were like in our country. In addition to my work in cardiology, I was selected to provide care for our returning Vietnam POWs who went to the two largest Naval Hospitals (Portsmouth, VA, and San Diego, CA). During this time, we also published one of the first studies on early treadmill testing 2-3 weeks after myocardial infarction, based upon our clinical experience and conviction that a more progressive return to physical activity was possible in many patients.

In 1973, Dr. Gilbert Blount recruited me to be the Director of Cardiac Catheterization at the University of Colorado. There, although my primary interest was in coronary artery disease, because of his earlier work in congenital heart disease, I performed cardiac catheterization procedures on both children and adults. In those days cardiac catheterization procedures and coronary bypass surgery were new and increasing rapidly. Dr. Spencer King, later to provide leadership for major programs at Emory, was in private practice in Denver for a year at that time, working with Dr. Schoonmaker, and together designed the multipurpose catheter – a modification of the Sones catheter which could be used percutaneously from the groin. This allowed those of us who had trained doing hundreds of procedures via cut-down and repair of the brachial artery from the arm to utilize percutaneous approach from the femoral artery in the leg.

After four years on the faculty at the University of Colorado, I moved to San Diego to head the Department of Cardiology at Sharp Memorial Hospital and to a position on the clinical faculty at UCSD where I stayed for 17 years. There, I directed the San Diego Cardiac Center and its cardiac catheterization laboratory which grew into one of the three busiest cardiac centers in the California, and continued work in interventional cardiology which was rapidly expanding at that time. I also participated with the team that performed San Diego’s first heart transplantation in 1986, and initiated innovative programs aimed at preventing heart disease. Between 1980 and 1994, we were a training site for teaching cardiologists in new techniques and participated in several interventional trials. At that time there were no organized fellowship training programs specifically for PCI, and teaching new techniques consisted of demonstrations at large hospital programs. We participated in the early rotablator trials, brief research in percutaneous laser coronary interventions, mitral and aortic balloon valvuloplasty and percutaneous cardiopulmonary bypass for high risk PTCA procedures. I was also a co-investigator on an NIH Ischemic SCOR Program with Dr. John Ross, then UCSD’s Chief of Cardiology, and performed early work with primary PCI for patients with STEMI.

You were a pioneering leader in the global organization of cardiology. How did this come about?

I was a member of the American Heart Association’s National Board of Directors and Vice President for AHA programs when I met Dr. Rod Starke, the Senior Vice President for Science and Medicine. He invited me to work with him and the AHA in the development of programs. This experience opened my eyes to the potential for organizational implementation of programs especially for cardiovascular guidelines. Later, as President of the World Heart Association, which oversees the activities of more than 200 societies and foundations of cardiology worldwide, I saw an opportunity to extend programs globally based on my experience with national programs at the AHA.

I recall preparing my AHA Presidential Address where, as the first interventional cardiologist to serve as AHA President, I planned to speak about the important contributions of invasive cardiology to cardiovascular medicine. At about the same time, the 4S study (Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study) showed for the first time that lipid-lowering with statins reduced total mortality. This was major news. In the early 1990s, there were prominent cardiologists who did not believe that cholesterol lowering therapy had benefit for patients, and this was hotly debated. For the first time, based upon the results of the 4S Trial, we had a way of significantly reducing mortality and treating atherosclerosis. My life had come full circle, from lipoproteins at NIH, to the cath lab at the Brigham, to a career focused on interventional cardiology, to the proof that treatment of blood lipids could prevent atherosclerotic events. The findings from the 4S trial were powerful. I decided to write my presidential address on risk-reduction therapies for cardiovascular disease and the need to change. And I challenged the community to think about the effective implementation of evolving medical therapies.

This development of several cardiovascular guidelines left me with feelings of responsibility and opportunity. The evidence from randomized control trials (RCT) could be summarized in guidelines and applied to patient care, and applied nationally, as well as to my patient care and teaching at UNC. There’s nothing like picking up a guideline when you are seeing a patient and asking, “who wrote this?” You learn to live with what you write. This was an important experience in understanding the need for implementation and quality improvement programs and their potential to broadly improve outcomes for patients with cardiovascular disease.

What were some of the challenges in putting together guideline committees? Is it hard to develop a consensus?

The two most important factors for an effective guideline committee are balanced representation among the members and creation of a strong evidence base. The more robust the evidence base – the less the need to establish consensus and the higher the likelihood for implementation. The ACC/AHA system of indicating strength of recommendation (I, IIa, IIb and III) and level of evidence (A, B, or C) makes it possible to distinguish between recommendations with strong supporting evidence (A) from those that are based upon opinion (C). It’s important to emphasize that lack of supporting evidence from randomized clinical trials (RCT) does not mean that a recommendation about treatment is incorrect – just that we have not confirmed it objectively with evidence. There are clinical situations where RCTs are not feasible and recommendations, out of necessity, must be derived from clinical experience and judgment.

When did you join UNC?

When did you join UNC?

In 1994, I was recruited to be Chief of the Cardiology Division at UNC-Chapel Hill. This was a pivotal point in my career for which I am indebted to Dr. Fred Sparling, Mr. Eric Munson and Dr. Stuart Bondurant, who recruited me and were responsible for major leadership for the UNC Medical School and Hospital. Within a year of my arrival, I was elected President of the American Heart Association. Especially memorable at that time was my interview with Bill Friday a remarkable man who contributed greatly to UNC during his nearly 30 years as UNC System President. From 2001-2003, I served as Chief Science Officer for the AHA while continuing my clinical and cardiac catheterization activities at UNC. In 2003, I resumed my full-time clinical role at UNC and served as Director of the Center for Cardiovascular Science and Medicine. The center expanded our participation in clinical trials and reached beyond cardiology to combine strategies involving the translation of basic science to clinical therapies for improved patient care. At that time, my major focus was on the development and evaluation of cardiovascular guideline implementation at the national and international level.

What are the 3 most important advances in the treatment of heart disease that you have seen in your career?

- Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery, technically less complex than heart transplantation, but having far greater impact in terms of the number of patients treated and receiving benefit.

- Percutaneous Interventional Procedures, 1) Primary PCI which has dramatically improved outcomes for STEMI patients, and 2) TAVR procedures for structural heart disease avoiding the need for cardiac surgery in many patients.

- Medical therapies, the first of which was statin therapy which, together with others, have revolutionized and advanced our programs in primary, secondary prevention and heart failure.

Tell us about the research you have been involved with. What research accomplishment has made the biggest difference for patients?

Without a doubt, the greatest accomplishment has been the work with cardiovascular guidelines and their implementation through quality improvement programs, both at the national and more recently international level. The first of these guidelines was for PTCA followed by many others including Secondary and Primary Prevention, STEMI, NSTEMI, and Hypertension and Treatment of Lipid Disorders. The most impactful were the Secondary Prevention and PTCA guidelines. Quality Improvement Programs sponsored by the AHA as “Get with the Guidelines” have also had a major impact on patient care. These outcomes are basically driven by the development of evidence-based guidelines. Adaptation of these programs are now benefiting patients globally. My early clinical research included myocardial blood flow, primary PCI for STEMI and NSTEMI, Mechanical Support and LVAD for cardiogenic shock and endstage heart failure, ACE Inhibitor trials for HFrEF after STEMI, and several statin-therapy trials.

What advice do you have for the next generation?

As a cardiologist, you know your patient in a manner that is highly personal and complex, which can occur over the course of time rather than during an isolated interaction. When I left for Chapel Hill in 1994, after 17 years in San Diego, I sent letters to more than 2,500 patients. Now I have seen patients in Chapel Hill for more than 25 years. Academic medicine is a demanding but rewarding career. The mixture of patient care, teaching and research brings a unique stimulation to daily life. If I had focused only on patient care, I’m not sure that I would feel as happy or as fulfilled as I do now, especially as my academic work has expanded to national and international programs.

What have been your biggest challenges and biggest accomplishments in your international cardiology work?

The extension and implementation of guideline development activities and quality improvement programs to countries with developing economies has been the most challenging and holds greatest potential to improve patients’ lives. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Developing evidence-based guidelines and implementing them broadly in health care delivery systems and countries with great variation in economic development requires dedicated teamwork. The opportunity to provide leadership for the World Heart Federation, and to chair several World Cardiology Congress Scientific Program Committees (Buenos Aires, Barcelona, Beijing, and Dubai) has been rewarding. Also memorable are the development of a coordinated effort for global programs aimed at reducing the toll of NCDs involving the major CV societies (ACC, AHA, ESC WHF), speaking at UN sessions in NYC, and interacting with WHO to implement programs with a focus on tobacco cessation, treatment of hypertension, and secondary prevention of CVD. Two international projects, CCC involving the design and conduct of quality improvement work in China over the last 20 years and the global REACH Registry have been especially challenging and productive.

Looking back on how the field has changed over the last 50 years, what are your hopes for the next 50?

My hope/dream is that preventive efforts involving behavior change (physical activity, heart healthy diet, and where necessary, legislative action (tobacco use, food labeling) coupled with early identification and treatment of risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, lipid disorders, obesity), will eliminate the current global epidemic of heart disease, stroke and vascular disease. ASCVD touches the lives of patients whose annual mortality in numbers exceeds that of COVID, and one that need not occur. We are the victims of the way we live. With strong efforts in primordial and primary prevention this can be changed to improve the lives of patients and avoid or significantly reduce the enormous costs of medical and surgical therapies which now overwhelm the medical systems of every country worldwide. An excellent initiative in cardiovascular prevention now underway in the UNC system is the use of EPIC as a platform for quality improvement to treat hypertension and identify cardiovascular risk. Global use of quality improvement programs founded on evidence-based guidelines, confirmed by results in countries with both developing and highly developed economies, can make this hope/dream for the prevention of cardiovascular disease a reality.