Meaghan Whalen, a second-year student in the Division of Speech and Hearing Sciences studying speech-language pathology, has repurposed communication resources in order to equip health care providers as they treat patients who face COVID-19.

Whalen, who returned home to Massachusetts to be with family at the beginning of the pandemic outbreak, began to organize academic resources as she transitioned to virtual learning. That’s when she rediscovered communication boards from a course taught by Penny Hatch on augmentative and alternative communication. With the guidance of a speech-language pathologist, the boards allow for those with difficulties communicating to get their wishes across. She immediately thought they might be a helpful tool for those facing COVID-19.

“When COVID patients are on vents, they tend to be on them for a while,” Whalen said. “I’ve never interacted with someone who was on a vent, but in a dysphagia course, I learned about all of the complications if you go on a vent,” Whalen explained.

Dysphagia, or difficulties in swallowing, can have myriad effects for patients who might need to swallow medication or eat and drink foods. Whalen explained that people who are put on a ventilator for additional breathing support would not be able to use their voice to communicate.

“For the most part, these patients might have a lot going on already and be disoriented or groggy,” Whalen said. “You need to be able to figure out what they want.”

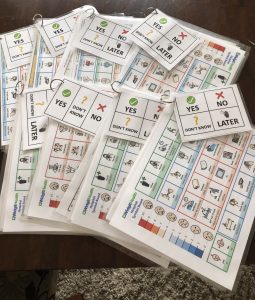

Whalen consulted with family members in health care to learn how effective the communication boards might be in a health care settings that treat COVID-19 patients. Patients who typically use the communication boards usually are able to get some of their needs across by alternative methods of communication, such as by blinking their eyes for yes or no, by pointing with a finger, or by employing other strategies. Whalen paired boards created by the Department of Allied Health Sciences’ Center for Literacy and Disability Studies with additional open-source communication resources and developed a kit for health care providers.

The communication boards, which Whalen hopes can be safely re-used, used are specific to patients in the intensive care unit. For instance, they may be able to help patients communicate questions or needs, such as “When is my tube coming out?” or “My IV hurts.”

“Care can be even more stressful when you can’t talk,” Whalen said. “Just think: when you lose your voice for one day, it’s so frustrating. Add to that being in a bed, unable to move, and being disoriented.”

Whalen and friend Meghan Kean from her time as an undergraduate student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst have created more than 30 resource packets, which they have distributed to providers at local hospitals in Boston and Connecticut.

Whalen said while there might not be a speech-language pathologist on a unit treating COVID-19 patient, she hopes that other health care providers will be able to employ the communication boards after reading the instructions.

“We want to make these available should someone need them,” Whalen said.

During a time when wearing a mask is encouraged, Whalen explained that wearing a mask could limit a patient’s ability to understand.

“So much of communication is you’re looking at someone’s face, and you’re connecting with them,” Whalen said. “In the heat of the moment, the providers are focused on saving their life. But if they know this person has the potential to use their eyes or their fingers to communicate, giving them the option to communicate is dignifying.”

Whalen knows about this firsthand—she was born with mild to moderate hearing loss and often wears hearing aids.

She explained that she often relies on visual cues, especially when she’s not wearing her hearing aids.

“It’s one more added stressor. I could go into a doctor’s office totally confident, but if I don’t have my hearing aids, that’s when [I] might feel a lack of confidence,” Whalen said. “It’s very easy to tell someone to be your own advocate, but for me, it took well into my first year of college to be my own advocate.”

Whalen said her coursework has taught her that all people still deserve to have the right to communicate. She said graduate school has taught her how broad the field of speech-language pathology can be and how versatile resources from coursework are.

“These boards—I was using these for my skilled nursing patients who had aphasia,” Whalen said. “It does us a lot of service to think ‘what is speech-language pathology?’ All of this is within our scope.”

She hopes that the boards are a way to contribute to families as they understand their loved one’s wishes, especially during a turbulent time.

“It just helps to know that even if they use it for five minutes, that someone could say what they wanted,” Whalen said. “For me, it’s the least I can do.”

Penny Hatch, PhD, CCC-SLP, is a research assistant professor at the Center for Literacy and Disability Studies, part of the Department of Allied Health Sciences. U.S. News & World Report ranked the master’s in speech-language pathology as #8 in the country in spring 2020.