Dr. Scott Donaldson talks with Dr. Ron Falk about cystic fibrosis, the testing and treatment for CF, and how people are living longer with the disease today. Dr. Donaldson is Professor of Medicine in the Division of Pulmonary Diseases and Critical Care Medicine. He serves as Director of the UNC Adult Cystic Fibrosis Care Center, and he is also the Medical Director for UNC Pulmonary Clinics.

“We’re asking patients to do two to three hours of therapy every day…and trying to encourage them to stick to these regimens that are so hard to fit into their school life, their work life, their family life. It’s really a big team effort working together to keep these patients going.”

– Dr. Scott Donaldson

Ron Falk, MD: Hello, and welcome to the Chair’s Corner from the Department of Medicine at the University of North Carolina.

This is our series where we discuss different genetic diseases with physicians who treat patients with these conditions. Last week we talked with Dr. Jim Evans about genetics and medicine; today we will talk about a specific genetic disease: cystic fibrosis.

We welcome Dr. Scott Donaldson, Professor of Medicine in our Division of Pulmonary Diseases and Critical Care Medicine. Dr. Donaldson serves as Director of the UNC Adult Cystic Fibrosis Care Center, and he is also the Medical Director for UNC Pulmonary Clinics.

Dr. Donaldson is an expert in cystic fibrosis. He treats adult patients at UNC who have this condition.Welcome, Scott Donaldson.

Scott Donaldson, MD: Thank you very much.

Symptoms of Cystic Fibrosis

Falk: What is cystic fibrosis?

Donaldson: Cystic fibrosis, or CF as we call it, is a genetic disease that affects multiple organ systems. Most prominently, it affects the lungs, but it also affects the pancreas, the liver, the intestinal tract, the reproductive tracts. It’s really, truly a multi-system organ disease that patients are born with.

Falk: How do people figure out that they have cystic fibrosis? What are the symptoms?

Donaldson: Cystic fibrosis can present in different ways. Some patients present with respiratory problems, some patients present with intestinal or nutritional problems, and it can come on at different points in life.

About fifteen percent of patients will be born with a bowel obstruction that we call meconium ileus. That’s essentially diagnostic of CF. Other patients may go much later in life before they develop any symptoms at all, and we occasionally will see adults who we are newly diagnosing CF.

Falk: What are those symptoms?

Donaldson: Respiratory symptoms would be cough, sputum production, recurrent pulmonary infections. Symptoms that are attributable to intestinal or pancreatic disease may be very abnormal stools—greasy, fatty, floating stools, inability to maintain weight, abdominal pain or bloating would be the most common symptoms.

Falk: If you took everybody who has CF—you described infants, and you described adults— what’s the general time of diagnosis?

Donaldson: It is getting younger and younger. Until a few years ago, newborn screening was not necessarily a part of every state’s program. As of about five years ago, newborn screening is conducted in all fifty states in the US. Most patients are

diagnosed in the first four months of life. Seventy-five percent of patients are diagnosed in the first two years of life.

How Cystic Fibrosis is Inherited

Falk: How does family history influence all of that diagnostic acumen?

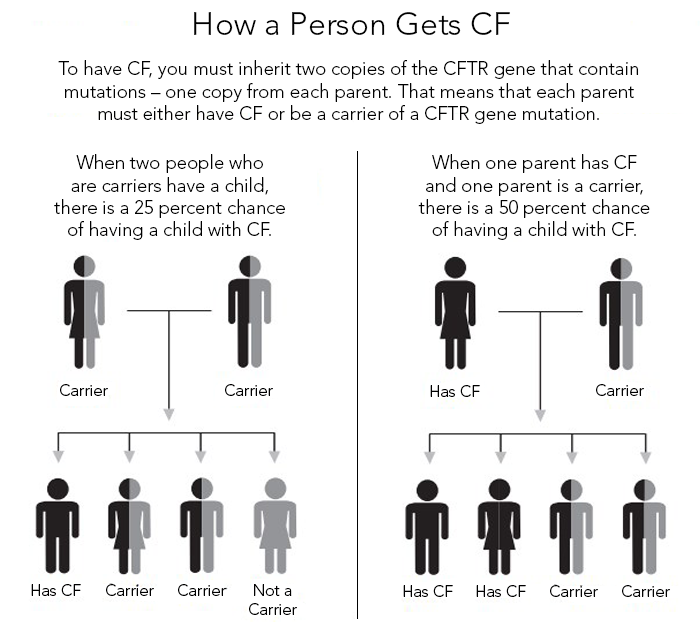

Donaldson: Right, because this is a genetic disease, but in particular what we call a recessive genetic disease, CF skips generations. There are many patients who know nobody in their family who had CF. It just pops up when two right parents get together, but certainly having a history of CF in your family lets you know that the mutations are in that gene pool and it’s more likely.

Falk: Just for our listeners, explain recessive.

Donaldson: Genetic diseases that are recessive means that you need two abnormal copies of that gene to have the disease. With CF, about one in twenty-five or one in thirty Caucasians are carriers and they have no symptoms whatsoever. They carry one abnormal copy. When two carriers get together and have a child—

Falk: Mom and Dad—each one has the affected gene.

Donaldson: Correct. When they, by chance, pass on that affected copy of that gene, to that child, there is a one in four chance that child will have CF.

Falk: Also, as a consequence of that thought process, if there are four kids, the other three would be potentially just fine.

Donaldson: That’s right. There would be a two in four chance of being a carrier, and a one in four chance of not even being a carrier.

Falk: At this point in time, the vast majority of patients in the United States are really discovered by newborn screening. There are a whole host of other diseases that are now being discovered by newborn screening of a blood sample taken in the Labor and Delivery.

Donaldson: That’s exactly right. The little blood spot taken from the heel is used to test for lots of diseases now, including CF.

Getting Tested for CF

Falk: If you know that somebody in your family has cystic fibrosis, and you’re a young adult, and are otherwise feeling okay, but may have some cough from time to time, when should testing be considered?

Donaldson: It’s a really good question. Certainly, if there are any symptoms that are unusual that could be suggestive of CF, that would be a reasonable thing to do, or at least see an expert, a pulmonologist—someone who understands CF, and knows the wide spectrum of symptoms it can present with. The more common time would be when you’re thinking about having a family. If you know that there are CFTR mutations in your family, you have relatives with CF, and you’re now thinking of having kids, it would be really wise, and most people would want to know if they’re a carrier or have CF.

Falk: How is the test done?

Donaldson: The genetic test done for CF is a simple blood test. We can do different things with the blood looking at panels of twenty-five or thirty mutations, all the way to sequencing the whole gene to identify essentially all of them.

Falk: Explain mutations in the CF gene.

Donaldson:That’s a really good question. First of all, cystic fibrosis is caused by mutations in one single gene called CFTR. Within that gene, however, there are more than 1,700 different mutations that can cause CF, so lots of mutations. A gene is essentially a blueprint for a protein, and when you make little changes to that blueprint, changing a “base pair,” missing a base pair, or missing a bunch of base pairs, all of them are different types of mutations that can cause CF. They make that protein not work normally.

Falk: A bit of DNA is transcribed to RNA and then translated into protein. Abnormalities, even tiny little ones, which look tiny, can be gigantic with respect to the eventual protein and how it functions.

Donaldson: Absolutely. It can be a little unpredictable, but it’s a huge part of what we’re doing right now, understanding how specific mutations cause problems in the protein.

Falk: The reason why you want to know that, as it turns out, and we’ll talk about treatment here in a minute, is that some of those mutations are now guiding what drug you use.

Donaldson: Absolutely.

Falk: That’s the fun, new world of therapy of cystic fibrosis.

Cystic Fibrosis Treatment

Falk: Let’s talk about the general treatment for somebody with CF.

Donaldson: Historically, we really treated CF by dealing with symptoms and what we call the downstream effects of the mutation. Patients, in their lungs, retain mucus, that mucus becomes infected, so we use medications that thin mucus to let people get rid of it more easily. We use a lot of antibiotics, whether it be oral, IV or inhaled, to treat those infections.

We have them do a lot of physical maneuvers to get rid of the mucus. We’re also having them take lots of medications to help them absorb their food, because their pancreas doesn’t work. We give them special vitamins, we give them nutritional supplements, so it really is a very complex, very arduous kind of regimen that we have patients do.

Falk: Unfortunately, some patients’ lungs fail, and then a lung transplant is considered.

Donaldson: That’s absolutely right. Every year, about 200 patients with CF require a lung transplant. It’s the lungs that typically are life-limiting in patients with CF. When you get to that stage, transplant is the only option.

Falk: The exciting part of treatment of CF is that understanding some of these mutations and the proteins that form may in fact guide specific therapy. There are some new drugs out on the market. Tell us about those.

Donaldson: The process that developed is really a great story, I think. In 2000, the CF Foundation, which is a big part of what we do in CF and now how therapies are being developed, decided that we’re just going to go on a fishing trip, and we’re going to invest in companies and ask them to look for molecules that do what we want them to do, with no knowledge of what those molecules might look like.

So, a big effort went into finding some of these drugs that make that CFTR protein begin to function again. In 2012, we had our first one approved, which was only applicable to about four percent of our patients, but it works spectacularly well. It taught us that if you can find a drug that makes that CF protein work, you can do really spectacular things for the patients. As time has gone on, we now are using combinations of drugs for the more common mutations.

There are now two drugs available for that. One is called Symdeko, it was just approved months ago. They are applicable to larger groups of patients, but as of yet aren’t quite as spectacular as that initial drug for that small group. Right now, we’re starting phase 3 trials of three drug combinations that appear to be spectacularly effective and are probably going to be applicable to more than ninety percent of patients.

Falk: That would be amazing.

Donaldson: That is amazing.

Falk: Who are the four percent of people who respond to the initial drug?

Donaldson: They are patients that have what we call “gating” mutations. This is, again, lots of different mutations, we group them in different types, but a gating mutation makes a protein that gets to where it needs to be in the cell. Then the CF protein, which is a channel—a kind of protein that controls how much salt in the water moves through the cell—it didn’t open up. So, it sits there like a closed gate that’s stuck and this medication made that gate begin to open and close like it’s supposed to.

Managing to Live with CF

Falk: Realizing that those drugs are being used and are in the offing for a bigger population, how, right now when you’re in clinic, and you’re seeing somebody with CF, what are the main concerns?

Donaldson: CF clinic is a complicated place. These are people who have dealt with the disease their entire life. They have a really serious illness, and because it does affect so many different organ systems, we’re dealing with a lot of different things. We’re dealing with their lung disease and measuring their lung function at every visit. We’re dealing with their nutrition, we’re dealing with their GI function. The combination of all of these medical problems impacts their life in lots of different ways. We’re asking them to do two to three hours of therapy every day, and as you can imagine, for more than a day or two…being cheerleaders and trying to encourage them to stick to these regimens that are so hard to fit into their school life, their work life, their family life, so it’s really a big team effort working together to keep these patients going.

The great thing, though, is we now have so much hope. We can talk about what’s coming and that gives them a reason to stick with what we’re asking them to do.

Falk: If you have a young person, a young adult, and they have CF, how do you manage to teach them how to take care of the disease themselves without their helicopter parents in constant attendance?

Donaldson: It’s a long-term process for sure to get to that point. We’re really trying to start early. We work together with our pediatric colleagues and pediatric pulmonary. We have a very formal, what we call a transition program. We have a transition coordinator whose job is really to begin the education process. Currently we’re doing it with our sixteen-year-olds, but we’re moving to younger and younger ages as well to start the education: “This is what you need to do to take care of yourself.”We then test them—they do absorb what we’re educating, and we re-educate them. That’s a constant process over years to get to that point. The adult clinic we also have to educate the parents that it’s important for these young people to take over their care.

Falk: Hard for a parent to do, though. Hard for a kid to do, and hard for a parent.

Donaldson: Absolutely.

How CF Affects Fertility

Falk: Does cystic fibrosis affect fertility?

Donaldson: It’s a problem especially for men with CF. Ninety-nine percent of men with CF are infertile. The tube or the duct that connects the testes to the rest of the world doesn’t form during fetal life, so sperm can’t get out. They make sperm but they can’t get out, so most men with CF are indeed infertile. They would have to see a urologist and fertility expert to actually harvest their sperm and do in vitro fertilization to have a biological child.

Women with CF are pretty fertile, though. Not completely normal—the mucus around the cervix is a little thicker, certainly if they’re very sick and malnourished they might not ovulate and will have reduced fertility. They will have kids – five babies a year or so just in our clinic. There are several hundred CF babies born to women every year.

Long-Term Outlook

Falk: In 2018, how long would somebody with CF be expected to survive? If these drugs work, what’s that going to do to long-term survival rates?

Donaldson: Survival with CF is really rapidly changing. I started in CF here at UNC in 1993. The expected survival of a baby born in 1993 was about twenty-nine years. Today, in 2018, the expected survival of a baby born today is forty-seven years. That presumes with no other major breakthroughs. We know the major breakthroughs are coming very, very soon. I would say forty-seven is a huge underestimate. This is speculative, and we’re making guesses, but I think if we start the drugs that we know are going to be here in a year or two in a little child with CF before they have much disease, they may have normal life spans.

Falk: That’s amazing. That’s a truly amazing story. Where can someone find out more about cystic fibrosis? What’s a good site to look at?

Donaldson: I think the best site is “CFF.org”. This is the CF Foundation’s website, and it just has a wealth of information for patients, for caregivers. We have data about all of our centers, and we can see how we’re performing, and we can connect patients to clinical trials that are going on, so it’s the best spot.

Falk: Scott Donaldson, thank you so much for spending time with me today.

Donaldson: Thank you.

Falk: Thanks so much to our listeners for tuning in. Next time, we will be talking with Dr. Amy Mottl about polycystic kidney disease, so stay tuned. You can subscribe to the Chair’s Corner on iTunes, SoundCloud, or like us on FaceBook.

Visit these sites for more information:

// var audio; var playlist; var tracks; var current; init(); function init(){ current = 0; audio = $(‘audio’); playlist = $(‘#playlist’); tracks = playlist.find(‘li a’); len = tracks.length – 1; audio[0].volume = .90; playlist.find(‘a’).click(function(e){ e.preventDefault(); link = $(this); current = link.parent().index(); run(link, audio[0]); }); audio[0].addEventListener(‘ended’,function(e){ current++; if(current == len){ current = 0; link = playlist.find(‘a’)[0]; }else{ link = playlist.find(‘a’)[current]; } /* run($(link),audio[0]); stops from going to next track */ }); } function run(link, player){ player.src = link.attr(‘href’); par = link.parent(); par.addClass(‘active’).siblings().removeClass(‘active’); audio[0].load(); audio[0].play(); }