Since 2008, July has been recognized as Black, Indigenous People, and People of Color Mental Health Awareness Month. Bebe Moore Campbell, who was a renowned American author who dedicated her life to advocacy for mental health in the black and other minority communities, is credited for this recognition.

Since 2008, July has been recognized as Black, Indigenous People, and People of Color Mental Health Awareness Month. Bebe Moore Campbell, who was a renowned American author who dedicated her life to advocacy for mental health in the black and other minority communities, is credited for this recognition.

Traumatic events in a person’s life can have lasting effects and go far beyond the immediate psychological and physical effects, which can be mitigated by protective factors and resilience, or compounded by other risk factors and vulnerabilities. Trauma experienced in childhood is particularly damaging and can alter development, including biology and behavior over the course of life, resulting in chronic illness in adulthood. Further traumas experienced as an adult can compound these health effects and can be passed on to subsequent generations (epigenetic inheritance). Black, indigenous and people of color may be particularly vulnerable with experiences and histories unique to their underrepresented groups. Scholarly research in adverse childhood experiences is helping physicians learn how trauma, whether from interpersonal, structural, and/or historical exposures, can work on neurobiological mechanisms that can lead to poor health, in part via maladaptive coping, affecting immunity, inflammation, learning and much more.

Amy Weil, MD, Professor of Medicine in the Division of General Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology, and medical co-director of UNC Hospital’s Beacon Program, has been working in the evolving field of trauma informed care over the past 17 years.

1.) Adverse childhood events are more and more recognized as mediators of chronic disease and outcomes. Can you describe what trauma informed care really is?

“Just to recap, Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are events or circumstances that are experienced as physically or emotionally harmful, or life threatening, and they can have lasting adverse effects on a person’s health. Examples include being exposed to or enduring abuse or neglect, violence, mental illness, parental separation and divorce, witnessing violence perpetrated against a parent, or the incarceration of a family member. While any one of these experiences can be devastating, having several of them can increase the negative consequences on health. These experiences can affect development and learning by ramping up the hypothalamic pituitary axis with enhanced sympathetic response and cortisol release, which in turn affects other neurotransmitters linked to development, mood, learning, immunity and inflammation. People in distress often seek ways of coping to survive that may be perceived as stigmatized behaviors such as substance use, maladaptive eating, risky behaviors, which further affect their health negatively. These effects can be worsened by additional intersectional (layered and compounding) traumas, including those imparted by overt racism as well as microaggressions which disproportionately affect the BIPOC people who are our focus this month. (As an ally, rather, than a group member, I am wary of generalizing in this way, but data from our COVID crisis does bear this out).

“Fortunately, trauma can also be undone by focused strategies.l At the individual level, these include positive, power sharing relationships, including those formed in healthcare, and body based coping strategies affecting the central nervous system, such as mindfulness, meditation and yoga that can be taught. It’s particularly important that we as healthcare providers do not retraumatize our patients (or ourselves) in the provision of care. Dismantling the structures that reinforce oppression, much more in the news and common parlance than ever before, is an enormous job with the power to affect the health of all of us, most especially BIPOC, whom we are focusing on this month. Also, we should never forget to focus on and notice the strengths our patients have, even as we are trained to search out and address pathologies; we can always help them to leverage strengths for healing.

“Trauma-informed care (TIC) recognizes that trauma experiences are ubiquitous and affect nearly everyone, as our current COVID experience underlines, even as it also underlines the differential experience of one’s trauma experience when compounded by others as we are seeing in the current acceleration/acknowledgement/noticing of racist behavior and their direct and unacceptable negative effects on health, with higher infection and death rates in Blacks and people of color (BIPOC).

“Further, TIC seeks to anticipate, acknowledge, and respond to the effects of trauma on people’s lives and, in so doing, mitigate the effects and foster healing. It has been defined as a strengths-based service delivery approach grounded in an understanding and responsive to the impact of trauma, that creates opportunities for survivors to rebuild a sense of control and empowerment, leading to improved health.

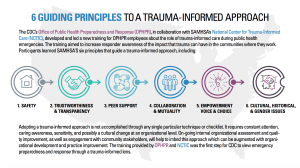

“TIC runs the gamut from more equalizing and non-stigmatizing communication strategies to less frightening/triggering physical exam techniques (like examining the thyroid by the patient’s side) to creating more welcoming institutional physical environments, as well as strategies that welcome patients who have experienced traumas into the healthcare setting, and reach out to them in their communities. It also reaches to the structural level of dismantling oppression in our community institutions that have led people to feel unwelcome and/or reach for maladaptive behaviors to cope with challenges. A key component involves provider care, as we are also subject to the risks and health effects of our own layered experiences of trauma, as well as those we may absorb from empathically caring for others. The government agency Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) reminds us to emphasize 6 components that are sensitive to the lived experience of people who have experienced trauma.

- Safety

- Trustworthiness and Transparency

- Peer Support

- Collaboration and Mutuality

- Empowerment, Voice and Choice

- Cultural, Historical and Gender Issues

“While these guiding principles are all important, our topic this month highlights number 6 – cultural, historical and gender issues. Without taking into account the historical and structural trauma experienced by members of a community we may unintentionally cause harm. The best way to understand the meaning here is to ask individuals from those groups. I was fortunate this past weekend to attend the Racial Equity Institute’s two-day anti-racism training and found it powerful and galvanizing, especially regarding learning some of our earlier American history from a racial equity lens. I highly recommend this experience.”

“I have also been fortunate to hear an On Being Podcast featuring Resmaa Menakem who has written a book I am reading right now, called My Grandmother’s Hands, where he describes the lived experience of racial trauma in the body and the source of its healing there as well. His grandmother’s hands picked cotton. Of interest, he and the author of White Fragility, Robin D’Angelo, have a podcast together.”

2.) One thing that stands out to me is your focus on wellness and awareness of providers of their own history of trauma and how that impacts patient care. Why is this important?

“As people, we all experience trauma. As our current experiences with COVID and the acceleration of racism showcase, it is a universal experience. In fact, healthcare workers are more likely than the general population to have experienced personal trauma; it may be what has drawn some of us to care for others. In addition, as our healthcare force reflects better our population demographics, more of our providers will have had the experiences of historical, community and structural traumas, particularly racism and microaggresions, in addition to the challenges of caring for patients with these same experiences. Educating our workforce and community to eliminate these additional stresses is imperative if we want to improve health.

“In serving patients, healthcare professionals may also develop vicarious, or secondary, traumatization through exposure to their patients’ stories of violence and trauma or, with wellness practices, they may also be able to experience post traumatic growth. Applying trauma-informed principles in clinical care, working to diminish trauma overall can help us move positively away from a focus on trauma towards healing centered engagement.”

“Just like I tell patients, there are things that have happened to you that affect your health today, but there are many things that we and you can do to help you to heal. The possibilities for healing are there just as much for us as for our patients.”

3.) How can we as healthcare workers use TIC not just this month, but every day, in our practices to address some of the unique mental health needs of minoritized communities?

“I think there are a few key ways. First, I just want to say that it is impossible to generalize about BIPOC or any communities, except to note that over all we have not served them/us as well. In your practice, never assume you know others’ experiences or identities. Ask individuals about their identities and experiences and behaviors with curiosity and respond accordingly. This is the basis of so called ‘cultural humility’. As we should with all of our patients, be especially welcoming and collaborative, check in to see if you are addressing patient needs. Be aware as the literature shows, that you may be under-ordering tests or procedures due to implicit bias and try to raise this to awareness and undo it. I am happy when I order a stress test on an African American woman and the test is negative; I would much rather be over ordering these tests than underdoing it, for their safety. In my patients whom I am aware have experienced segregation, this means taking more time to build trust (and realizing they have good reasons to be wary), using teachback to assure understanding and working harder to advocate to be sure their needs are met.

“Though not unique to BIPOC communities, I encourage you to practice TIC as a universal precaution. You cannot tell who is a trauma survivor or even who identifies as being from a minoritized group. Be aware to use collaborative interview techniques, offering patients choice and giving them control as much as possible. For the exam, there are some great resources to learn more, but draping respectfully, asking permission, checking in and stopping if there is discomfort, using neutral language for body parts are key points for everyone. Educate yourself (or invite me to!) on these techniques.”

“Work in general to destigmatize mental health concerns and inquire about them. Our general medicine clinic has focused Depression and Anxiety Care programs and we regularly inquire and address these issues as well as Intimate Partner Violence, which can lead us to learn more about patients’ lived trauma experiences.

“As we understand more about the effects of structural factors on health, we are developing innovative programs in our clinic and in education to reach out to patients and learn more about and address their social contributors to health needs. The more we know about patients’ experiences and contexts, the better we can serve them and give them some breathing space to heal.

“Connected to understanding contexts, always be curious about patients you perceive to be nonadherent or ‘challenging’. Rather than judging, ask them about and try to assist with barriers. You may uncover challenges you can address that may be rooted in prior traumatic experiences that have made it hard for them to connect with you and/or structural barriers they did not feel comfortable bringing to your attention.

“I think most important is that we continually educate ourselves and our learners on ways that we can do better. Absolutely essential is to seek inputs from individuals with these lived experiences to inform our learning.”

4.) How did you personally become drawn to this field of study, to apply an academic lens?

“You know, I am learning more about this every day. I realize that I have been working in this field for over 30 years. After college, I worked in a long term psychiatric hospital and noticed the pervasiveness of trauma and also the potential for healing in the teenagers there. One young man, who had been abandoned by his family and spent most of his time under his bed except when I accompanied him to the weight room, later went on to become a social worker. I learned more about the dynamics that might have been at play from Rape Crisis Training.

“In my childhood, I remember learning the story of the Holocaust and realizing that as a Jewish person, just for having been born, in my parents’ lifetime, if we had lived in Europe I could have been rounded up and killed, irrespective of my beliefs, perception of my own identity or behavior, simply for being, as seen by someone else. I also heard stories from my family and experienced anti-Semitism myself. The absolute unfairness of this differential treatment/oppression affected me deeply. I think it ignited passion and empathy to learn more and fight against any kind of injustice perpetrated on others simply for being who they are, whether it took the form of sexism, heterosexism, xenophobia or racism and even more, to celebrate and embrace difference.

“The learnings about how trauma is situated in the body resonate with me as I feel a visceral angst about what has been going on most recently in our world related to disparities. I am truly fortunate to be able to channel this passion to productive use in the practice of medicine, education of others related to trauma, and work to make our system more friendly and healing for all.

“I am deeply saddened by the loss of John Lewis and so inspired by his courageous life and his words that seem emblematic in this time as related to healing and justice: ‘Though I am gone, I urge you to answer the highest calling of your heart and stand up for what you truly believe.’“

5.) If given unlimited resources, how would you suggest we eradicate the need for TIC?

“Thank you for asking this question. No one has ever offered unlimited resources to solve the enormous problem of trauma!

“I think equalizing the social foundations, with significant financial investments in BIPOC communities is critical as this could fundamentally alter the environments which contribute to adverse childhood experiences and ongoing re-traumatization. In this light, one can see reparations as a way to work toward equalizing the social and moral foundations of our country.

“Righting social attitudes about power and control related to race, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religious affiliation, stigmatized behaviors are important especially as they relate to community sanctions/norms (different from policing) against discrimination. Early intervention, such as being enacted by Dr. Nadine Burke Harris in California, where she is Surgeon General, is another approach to rebuilding the world in a more equitable way that builds resilience before troubles develop.

“Adopting a trauma-informed approach cannot be accomplished through any single technique or checklist. It requires constant attention, caring awareness, sensitivity, and likely a cultural change at the organizational level of many of our institutions. This would include early engagement with community stakeholders, ongoing internal organizational assessment and quality improvement to be sure we are moving in the right direction.”

“From our immediate perspective, training (and holding accountable) health providers and teachers to do their jobs with a lens that understands all kinds of traumas, and includes space, and even a mandate to cultivate their own wellness and healing, could be a big help as could changing some of our institutional practices to be more trauma informed, welcoming, healing and at the very least, less frightening.

“Becoming trauma-informed is a journey rather than a fixed set of interventions. Trauma affects all of us directly and indirectly, and trauma-informed care can create an optimal healing environment for a patient, a patient’s family, learners and the healing provider and staff.”

Resources:

Mental Health Apps Geared Toward People of Color

Race and Healing: A Body Practice

My Grandmother’s Hands by Resmaa Menakem

Advancing Curricular Content and Educational Context

Book Review: Trauma-Informed Healthcare Approaches: A Guide For Primary Care

A Novel, Trauma-Informed Physical Examination Curriculum for First-Year Medical Students

A novel, trauma‐informed physical examination curriculum

From Treatment to Healing: The Promise of Trauma-Informed Primary Care

The Future of Healing: Shifting From Trauma Informed Care to Healing Centered Engagement