UNC-Chapel Hill and UC San Francisco scientists have published work in Nature, laying the groundwork for better anti-itching medications with fewer side effects. The work was led by UNC School of Medicine scientists Bryan L. Roth, MD, PhD, Jonathan Fay, PhD, and first author, Can Cao, PhD, postdoc in the Roth Lab.

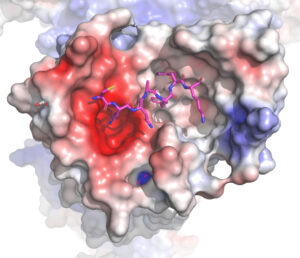

Ever wonder what’s going on when you get itchy skin, whether from a rash or medication or some other bodily reaction? And why do some strong anti-itching medications make us nauseous, dry-mouthed zombies? Scientists at the UNC School of Medicine and the University of California at San Francisco conducted research showing in precise detail how chemicals bind to mast cells to cause itch, and the scientists figured out the detailed structure of receptor proteins on the surface of these cells when a compound is bound to those proteins.

“Our work provides a template for the design of new anti-itch medications,” said Roth, the Michael Hooker Distinguished Professor of Pharmacology. “Also, our research team did a truly remarkable job showing precisely how chemically distinct compounds induce itching through one of two distinct receptors known to be involved in itching.”

On the surface of cells sit receptor proteins you can think of as complex locks. When a chemical key enters the lock, not only does the cell “open,” but the chemical causes a chain reaction of signals inside cells. Many chemicals do this, from naturally occurring dopamine in the brain to caffeine and cocaine.

When it comes to itch, Roth’s lab identified two receptors called MRGPRX2 on the surface of mast cells and MRGPRX4 on itch-sensing neurons that live in connective tissue and play roles in allergies, immune tolerance, wound healing and other factors in health and disease.

Several drugs unintentionally flood these receptors to trigger the release of histamines, causing the side effect of itching. Drugs such as nateglinide for diabetes, as well as morphine, codeine, and the cough suppressant dextromethorphan are known to cause this reaction. Antihistamines are designed to tamp down the itch response, but they and other anti-itching medications do so clumsily, tripping other cell signaling pathways to cause side effects such as drowsiness, blurred vision, dry mouth, nausea, etc.

“Knowing precisely how all this plays out at the molecular level will help us and others create better ways to control the role of these two receptors in itchiness and other conditions,” Roth said.