UNC School of Medicine researchers led by Mauro Calabrese, PhD, have developed a way to categorize mysterious RNA molecules by their likely function, a big first step toward quickening the discovery of their roles in human health and diseases, such as cancers.

CHAPEL HILL, NC — Scientists from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine have developed a powerful method for exploring the properties of mysterious molecules called long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), some of which have big roles in cancer and other serious conditions. Until now, scientists have lacked the proper methods for identifying the functions of the tens of thousands of different lncRNAs produced in human cells. So far they’ve characterized only a few hundred of these molecules – a tiny part of the vast terra incognita they represent.

Published in Nature Genetics, UNC scientists discovered a hidden code that relates the molecular makeup of lncRNAs to what they actually do, and the researchers developed an algorithm to quickly categorize lncRNAs by their likely functions.

“Long non-coding RNAs are part of what you might call the ‘dark matter’ of the genome, and this tool we’ve developed should help us understand much better how they work in health and disease,” said study senior author Mauro Calabrese, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacology and member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Genetic information in animals and plants is stored in DNA, and cells make use of that genetic information by transcribing the DNA into closely related molecules known as RNAs. Many RNAs go on to be translated into proteins. But scientists in recent decades have been forced to reckon with the fact that less than 2 percent of the genome is used that way. Most of the DNA is transcribed into RNAs that do not encode proteins. These are called non-coding RNAs, and the ones over 200 nucleotides in length are classified as long non-coding RNAs.

Many of these RNAs bind to proteins or other molecules to switch genes on or off, thus regulating cellular processes. One of the best known lncRNAs is called Xist, which is important for normal development in females. High levels of another called MALAT, have been linked to more aggressive and metastatic cancers. On the whole, biologists are sure that many lncRNAs have key regulatory roles whose disruption contributes to disease. So far, however, they have characterized the functions of only a small fraction of the many thousands of lncRNAs that are thought to exist in mammalian cells.

One reason biologists have been slow to understand what these molecules do is that a lncRNA’s function is not readily apparent when you study how it’s put together from its sequence of nucleotide building-blocks. Often two lncRNAs with similar functions appear to have very different sequences.

Calabrese and his team, including first author Jessime Kirk and Peter Mucha, PhD, professor of mathematics and applied physical sciences in the UNC College of Arts and Sciences, tried to decipher the otherwise obscure relationship between lncRNA sequence and function. They started with two key clues: Firstly, there is evidence that lncRNAs function mainly by binding to proteins. Secondly, RNAs connect to proteins using short sequences within their overall structures.

“We reasoned that the presence of protein-binding sequences in a lncRNA would be more important than their relative positioning within the lncRNA,” Calabrese said. “This notion ended up being true, and allowed us to succeed where more traditional approaches have failed.”

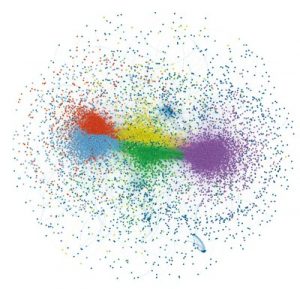

The team developed a computer-based method called SEEKR to find and compare protein-binding sequences they called “kmers” in lncRNAs, regardless of the kmers’ precise locations. The team found that about half of all human and mouse lncRNAs could be grouped into five different communities, based on similarities in their kmer content. The kmer-based approach also could help predict where lncRNAs are normally found within cells and to what kinds of protein they bind.

“We can now take sequence information from a well-studied lncRNA, and use it to discover lncRNAs that may be functioning through a related mechanism. In a way, it’s like being able to finally understand the different scripts in the Rosetta Stone.” Calabrese said.

Congratulations to Jessime, Mauro and all the other authors not he paper!

Other authors were Susan Kim, Kaoru Inoue, PhD, Matthew Smola, PhD, David Lee, Megan Schertzer, Joshua Wooten, Allison Baker, Daniel Sprague, David Collins, Christopher Horning, Shuo Wang, Qidi Chen, and Keven Weeks, PhD. All were at UNC-Chapel Hill when this research was conducted.

Citation: Kirk JM, Kim SO, Inoue K, Smola MJ, Lee DM, Schertzer MD, Wooten JS, Baker AR, Sprague D, Collins DW, Horning CR, Wang S, Chen Q, Weeks KM, Mucha PJ, Calabrese JM. Functional classification of long non-coding RNAs by k-mer content. Nat Genet. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0207-8. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 30224646.